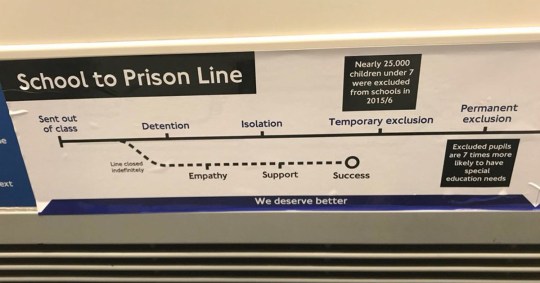

The term ‘school to prison line’ is a phrase used in youth work circles which has invariably become a reality for the thousands of working-class boys that are excluded from school.

For far too long, a broken education system and justice system has meant that the destiny of excluded teenagers in the UK is a life of crime. It has become such a stain on our system that the former Director-General of the Prison Service, Martin Narey, said “the 13,000 young people excluded from school each year might as well be given a prison sentence” in 2001.

When does this phenomenon begin?

To fully understand the prison-to-school line, we must start at the very beginning; being sent out of class. Being told the leave a classroom is the first step to being permanently excluded from school. Removing a child from a learning opportunity is unquestionably counterproductive. It serves as a way to further increase the educational gap between students from more affluent backgrounds, who are less likely to have behavioural problems at school, and students from poorer backgrounds. At this very moment, our educational system should work to empathise and support our students, however, it instead criminalises and punishes the student.

The next step in the School-to-Prison Line is detention and isolation. Again, instead of support being offered to students who continue to get into trouble, sometimes for nonsensical reasons, schools will simply brand the child as a lost cause and find any excuse to temporarily exclude them. In 2017, there were over 410,000 fixed-term exclusions, this represents a 52% increase since 2013/14. This rise has, in part, been driven by the forced academisation of schools; headteachers are no longer held accountable for the students they choose to exclude.

Academisation is the process by which local authority maintained schools turn into academies. Depending on circumstances, a school can become an academy either by the ‘academy sponsorship’ route or on the ‘academy conversion’ route

What happens next?

Once a child has been temporally excluded, it is just a matter of time until they are permanently excluded. Excluded pupils are 7 times more likely to have special educational needs, it is clear that headteachers have become judge, jury and executioner, passing sentences over students they could never understand.

After being permanently excluded, children are sent to a pupil referral unit (PRU). At PRUs, teachers can focus their attention on trying to support students with a behaviour problem. However, the problem with PRUs are that they have become a breeding ground for gangs and criminal activity. This isn’t the fault of PRU institutions, it is the direct result of grouping together students with challenging behaviour. It is for this reason that only 1% of pupils at a PRU get 5 GCSE, and 85% of them end up in a young offender institution.

Young offender institutions operate as pipelines to prisons and with a 70% reoffence rate, many of the young offenders will end up in prison. At this point, the individuals will have become institutionalised and will struggle to escape a life of crime without the necessary support. If we spent the money it costs to exclude children from schools on measures to keep them in mainstream schooling, we could more than halve the number of children forced into a life of crime.

Dee

Dee