As elections loom, Biden’s new running mate Kamala Harris proposed a $2,000 COVID stimulus cheque and “lots more money” for Americans to get back on their feet. She, among many other leading Democrats, are proponents of wealth taxes to finance ambitious initiatives from poverty to climate change.

Most detailed was Elizabeth Warren’s plan outlining a 2% levy on $50 million fortunes and 3% on those over $1 billion. This was claimed to fall on 75,000 U.S. households (0.1%) and raise $2.75 trillion over 10 years. Given the top 40% of wage earners in America pay 106% of the taxes, and the bottom 40% pay negative 9 per cent because of tax credit transfers; the wealthiest 0.1% are not only the job creators, paying both the tab and tip for the table, but they number too few to finance the ambitious Democrat spending designs. America is by no means the first to dabble with the idea of wealth taxes. Europe’s experience with them has been counterproductive, so what makes America the exception?

Feasibility

With so much money at stake, the wealthy will have greater incentive to commission smart advisers to mitigate their liability, implementing tax planning that only highly paid lawyers and accountants can devise.

Questionable appraisals, valuation discounts for illiquidity and loss of controlling stake in business ventures or over assets; using trusts to divide assets among many family members while the founder retains substantial control; charitable devices offering significant income to the donor and their beneficiaries; inevitable, built-in backdoor loopholes in return for political donations; among other complex devices known only to sophisticated investors – all of which are but a few considerations any sensible bureaucrat should take note.

Privately held businesses are notoriously difficult to value, meaning in effect, the Taxman would have to prove any given taxpayer’s valuation is unreasonably low. This could be because many of these 75,000 households own private companies not listed on the public markets, or it could be the challenges in accurately valuing even those listed companies.

Stock prices reflect the aggregation of what people think the net present value of the future cash flows of those companies are. Listed shares is only money on paper, not tangible mountains of gold sat in a lair guarded by dragons. Forced sales of shareholdings to appropriate that ‘wealth’ would cause price crashes on those stocks as speculators drive down the value of their holdings to take advantage of the new wealth tax. The taxpayer would not receive the same money as their ‘net worth’ would have had us believe.

What has been the experience of other countries?

By the early 1990s, a dozen European countries had wealth taxes. By 2018, that number had dropped to 3. All were dropped because they failed, sometimes costing twice that of the net revenue from levying them. Tax revenues were much lower than anticipated and frequently failed to meet their redistributive goals because of efficiency and administrative concerns.

Switzerland

Switzerland has the largest wealth tax. A 2016 National Bureau of Economic Research report looked at the effects of wealth taxation on reported wealth in Switzerland and estimated that “a 0.1 percentage-point rise in wealth taxation lowers reported wealth by 3.5% in aggregate.” (Or that a 1% wealth tax lowers reported wealth by 34.5%.)

France

France began their wealth tax in 1981 during the radical 5TH Republic during which they increased minimum wages 10%, nationalised top companies and banks and began wealth taxes atop revenue taxes to answer the Petroleum Crisis of 1971 that ended their long period of prosperity: ’30 glorieuses’.

The results were terrible. Only 2 years later they started austerity and later lost by landslide rejection in 1986 elections.

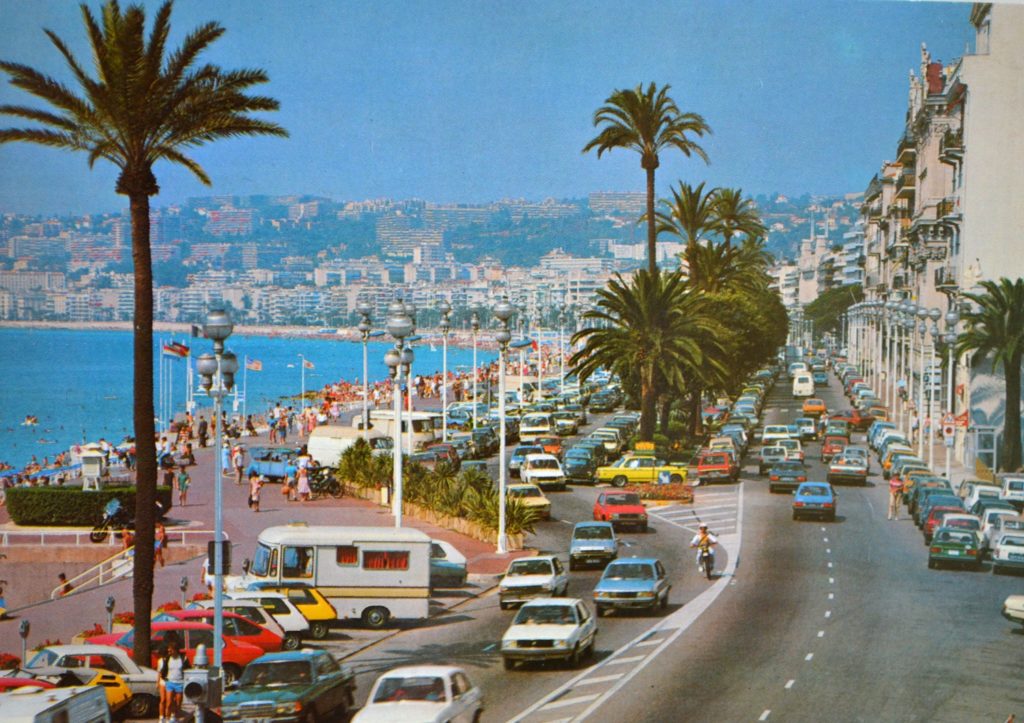

Every radical economic decision was rolled back, except the ‘Wealth Tax’ because no government could be seen to be a “friend of the rich” til Macron bit the bullet and replaced it with Impôt de Solidarité sur la Fortune (ISF) 2018 on estates worth €1.3 million+. This was on revenue and on the estate, presenting an exclusively French dual tax neighbouring countries didn’t have. So what did the richest people do? They left.

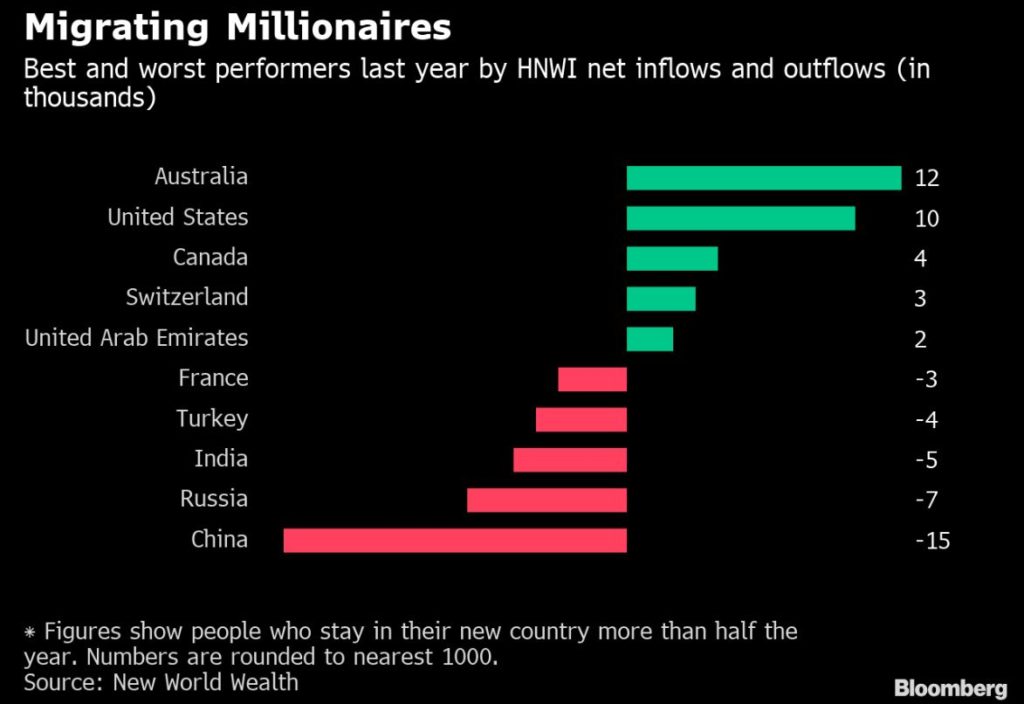

France lost all the taxes, investment, and the consumption they brought with. All France’s neighbours have benefitted from France’s Rich for nearly 40 years as tens of thousands of millionaires left every year.

The wealth tax brought in €4 billion (1% France’s total tax revenues) but costed far more. French economist Eric Pichet estimated that this ended up costing the French government almost twice as much revenue as the total yielded by the wealth tax

The unintended consequence of this tax was to disincentivise people to become rich in the first place. Why bother accumulating more since the government will take it all? Fewer people took entrepreneurial risks to create things, meaning less value and employment for France.

Lawyers always win

To limit the fallout, there were many tax loopholes created by the French government to try and retain or lure back the rich. This was hypocritical at best, inefficient and only really benefitted the tax lawyers with the French people footing the bill.

There are more efficient and subtle ways to part the Rich people with their money without them leaving the country and that’s what the US government should seek.

Alternative Perspective

America maybe the exception because it will pursue a no loopholes approach. Where European nations exempted art and antiquities on grounds of valuation creating incentives to allocate funds there, the US won’t be so lenient.

Warren’s proposal is also limited to the clearly super rich. A smaller group unable to organise effectively for exemptions.

Where Europe had freedom of travel, U.S. law taxes its citizens wherever they are. With the “exit tax,” which would confiscate 40 percent of all a person’s wealth over $50 million if they renounce their citizenship, it might just work….question is, when the dust settles, will we want it to?