Monday was America’s Labor Day to emphasise the dignity of labour. Although different to union strikes in 1894 that inspired the holiday, America’s Civil War “General Strike” offered a powerful example when the law prioritises property over people. England was forced to reckon with this dilemma many decades before, but what really caused slavery to be abolished in 1833, some 30 years earlier than in the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave?

We are told colonisation was not of any major economic benefit to Britain, but a benevolent act to civilise the world. A YouGov poll in 2014 found 59% respondents thought the British Empire was something to be proud of. We are told the slave trade was, of course, Islamic. The British, simply the middlemen. Not to forget Britain stopped it with the Abolition Act of 1833, paying a substantial sum in compensation to slave owners to facilitate this. Was slavery going to inevitably end because it wasn’t a financially viable system having already laid the foundations for a more efficient system of industrialisation, or was it the moral awakening of a truly global superpower throwing its weight behind abolition?

Abolition, emancipation and manumission

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 formally freed 800,000 Africans who were then the legal property of Britain’s slave owners. Less well publicised were clauses within to compensate the 46,000 slave owners £20 million by the British taxpayer for the loss of their “property”, representing 40% of the government expenditure for 1834. A modern equivalent of £17 billion. Besides the slaves and their descendants receiving nothing, they were also compelled to provide 45 hours unpaid labour each week for their former masters for four years after their liberation. This meant the enslaved paid part of the bill for their own manumission alongside their future generations paying off the interest on the debt undertaken by the British government.

Slavery benefits to Britain

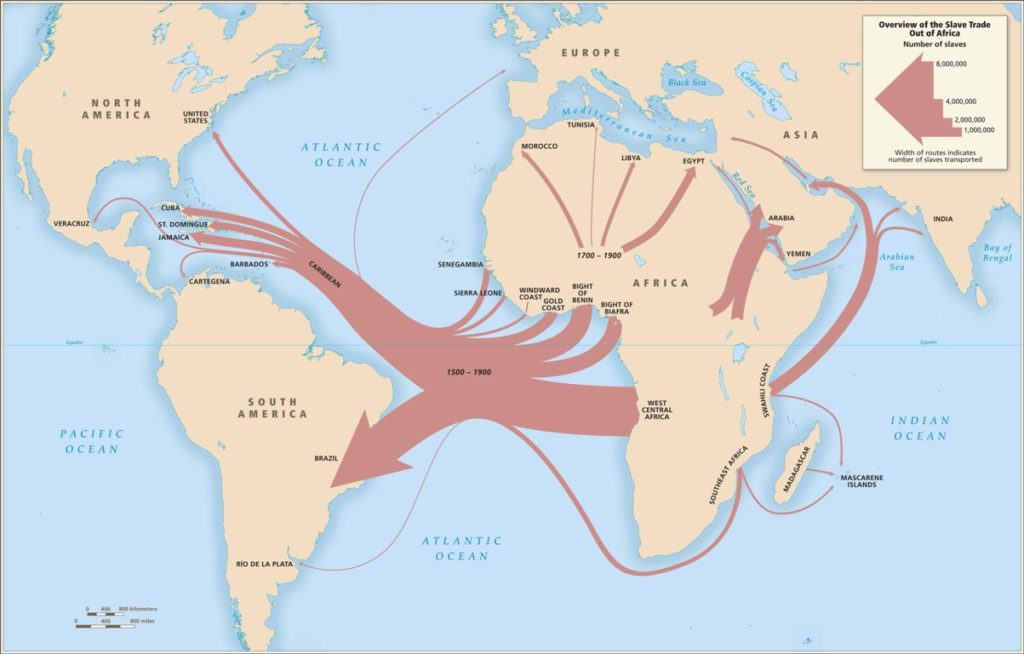

From 1607 to 1807, about 2.5 million slaves passed through Britain. Loose estimates put the value of a slave at £100 in 1807, with half dying, unsold, lost or escaped, rendering £50 per slave. This leaves £125 million, equivalent of £610 billion in today’s money, making the trade worth £3.05 billion a year.

There were certain costs involved, not least purchasing them from the African slave kingdoms, who in turn, purchased them from African dealers. The currency ‘bars’ were not always accepted. Ships and crews were expensive. The profits went on products from the Americas. Many ships were lost to piracy, went rogue, or lost to rough weather or navigational error. They took a long time to complete the ‘Atlantic triangle’. The UK government and its taxpayers policed the seas via their general taxation, with the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron costing more to upkeep than the profits from 200 years of the slave trade. Of the British slave trade, a third of revenues, some £183 billion went toward British goods and services. Over 200 years, £915 million, sufficient to make a fair few individuals very rich, keep ports and supporting industries busy. But for the incalculable cost to human life and dignity, there really wasn’t all that much to show for it.

Foundations for Industrialisation

Caribbean academic, Eric Williams, published ‘Capitalism and Slavery’ in 1944 in which he argued the slave trade was critical to get the industrial revolution off the ground. For instance, James Watts invention of the steam engine was financed by plantation owners. He suggested slavery was abolished primarily in the 1830s, not because of our moral awakening, but because it was no longer economically advantageous. The margins between buying African slaves against what they could be sold for in the Americas was no longer profitable by 1800. It only lasted as long as it did because of subsidisation by the British taxpayer and the alternative incomes raised around the Empire.

The historian, David Richardson, concluded the slave trade made up 1% of domestic investment in Britain. While economic historian Stanley Engerman argued that at its highest, giving the benefit of the doubt to Williams’ figures, that the West Indian plantations contributed at most 5% to British national product in any given year.

If industrialisation made Britain wealthy, and not the slave trade, can we say the slave trade was vital to the industrial revolution in the same way as the colonial extraction of colonies facilitated the industrialisation of the world? India’s trade surplus financed the invasion of China in the 1840s, suppressing uprisings in Sudan, Boers, India itself in 1857, the Zulus and countless other pursuits to force the world to trade on Britain’s own terms.

Other players

Germany played the briefest of roles in colonialism and slavery, yet industrialised successfully. Portugal was the pre-eminent slave exporter over a longer period than Britain, yet entered a slow economic and political decline 150 years prior to Abolition. Spain, whom profited from both slavery and vast gold and silver shipments, barely industrialised at all until technological transfer from elsewhere. The Ottoman Empire had a fully fledged slave economy for half a millennium, all without having their own industrial revolution. It appears denying vast swathes of your population the ability to hone their own skillsets or earn their keep prevents them from meaningful participation in consumption or growth. The real accruals appear to be to individuals, rather than the state and its average citizen. The British state paid the costs of associated wars and security, and the costs of Abolition, taking on a vast loan on which the interest was finally paid off only recently.

As the case of the Ottomans and Germany has shown, the wealth built was less to do with slavery that has dated back through every known society to 5,000 B.C.E. And yet, only in a small snapshot of this 7,000 years have certain nations developed as the West did. This would support industrialisation as the foundation for modern wealth creation, albeit the mercantilist slavery seems to have laid the foundations for this.

The possibility to begin the end to slavery was only achieved by a superpower that ‘dominated’ the whole world. Before then, no other society had the influence to drive such a change in the course of history. Within a few decades, a prevailing universal condition since the Neolithic times had reversed course to the extent that the mere sight of British sailors in foreign slave market ports would create a rebellion. Despite this, it took 100 years and the might of all the Western nations to end slavery globally. This took enormous time, money and effort to attempt to end slavery globally without any profit for Britain. It were only made possible by the power, influence and scope of the Empire, without which, it is quite possible slavery would remain commonplace today. And not because they foresaw the gross economic inefficiencies of slavery against liberated individuals partaking in free markets, but because it was the right thing to do.