Since the coronavirus pandemic started, the Office for Budget Responsibility estimates the government has spent over £100bn in response. From the furlough scheme, to ‘eat out to help out’. Whilst some of these schemes are welcome, questions are being raised about where the government is getting all of this money from, and when it will need to be paid back.

The government has three sources of income:

Taxes

Money paid by individuals and businesses. this includes VAT, income tax, national insurance and more. Since the coronavirus pandemic made its way to the UK, the Government has made significant cuts to taxes. This includes a cut in VAT from 20% to 5% in the hospitality sector along with a stamp duty cut for properties below £500k.

Borrowing

The government will have to borrow money if it is spending more money than it receives in taxes. For example, if the government collects £100bn in taxes and had a total expenditure of £150bn then it would need to borrow £50bn. This is known as a budget deficit.

Printing Money

The government can create more money to finance spending. This can be done by getting the Bank of England to print more money; the bank of England will then use this ‘new’ money to buy bonds issued by the government. The government will then use this money to finance its spending.

How does the government borrow money?

According to the Office of National Statistics, the government will borrow £298.4bn in this current financial year (April 2020 to March 2021), this is 5 times higher than the government borrowed in the last financial year. The reason why government borrowing is at a record high is to pay for the furlough scheme, bail out major industries and to invest in infrastructure projects that will boost the economy.

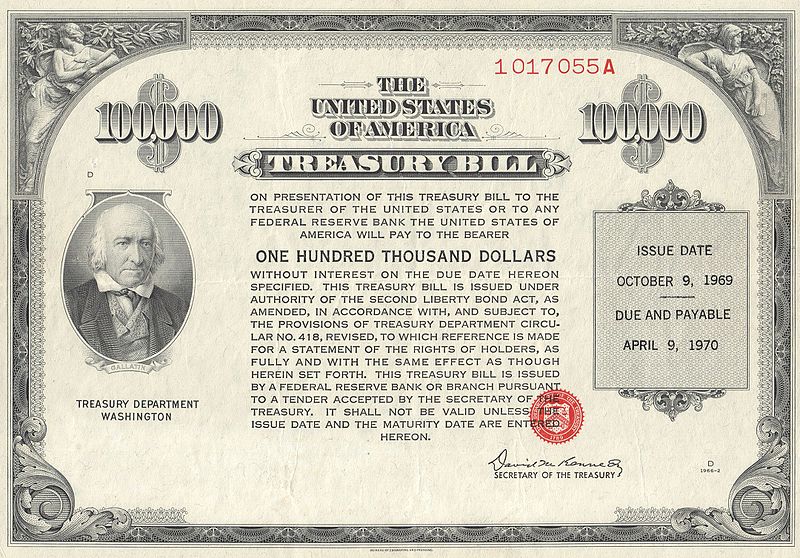

When the UK government wants to borrow money, it will create something called a bond. A bond is a government ‘I owe you’. This means that an individual is lending the government money which must be paid back in full. Every government bond has a cost, an interest rate and a maturity date.

The cost is how much the individual is agreeing to lend the government. For example, if a bond cost £1000, the individual purchasing the bond will be lending the government £1000.

The interest rate is the percentage paid to the individual for holding the bond every year. For example, if an individual buys a bond that costs £1000 and has an interest rate of 10% then the interest paid by the government, to the bondholder, will be £100 every year.

The maturity date is how long the bondholder has to wait until their money is paid back in full. For example, if an individual buys a bond in 2015 that costs £1000 and has a maturity date of 5 years, the government will have to pay the bondholder £1000 in 2020.

Who lends money to the government, and why?

Pension funds and insurance companies are the two biggest buyers of bonds. This is because lending money to the UK government is seen as a low-risk investment. It is seen as low risk because the UK government has never failed to pay its debt and has a good credit rate. Private investors will also get a steady return on investment, as interest is paid by the government yearly.

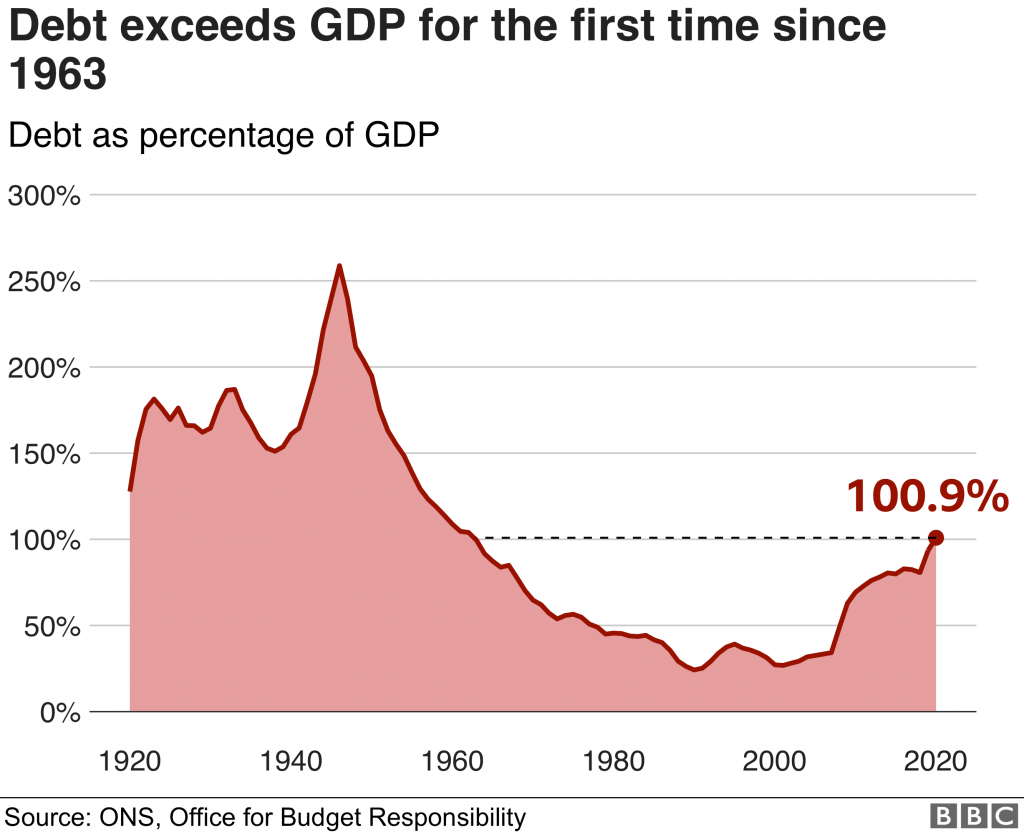

The total amount of money the government owes is known as the national debt. Currently, the UK national debt is £1.95 trillion. When a country is unable to pay back its debt it is called “defaulting”: the national equivalent of going bankrupt.

What happens if the government cannot pay back its debt?

If the UK were to default on its debt then its international reputation and creditability would plummet.

Banks and pension funds would struggle or be unable to give the customer back their money, as they are the biggest purchasers of UK bonds. Foreign lenders will also be hit, as there is no international law or court for settling sovereign defaults. When Argentina refused to pay £1.1 billion-plus interest of the money borrowed there was very little investors could do to force the Argentinean government to pay. The only thing investors could do is move their money out of the country, which would cause the value of their currency to fall. Furthermore, defaulting would mean the UK government would also find it very difficult to borrow money from lenders in the future, and foreign governments could impose sanctions on the UK until they agree to pay.