What do Andrew Jackson, Samuel J. Tilden, Grover Cleveland, Al Gore and Hillary Clinton all have in common? If you guessed that they all share the unfortunate fate of losing presidential elections despite winning the popular vote, you’d be absolutely right. There’s a fun piece of trivia to go and share with your friends, they’ll absolutely love it.

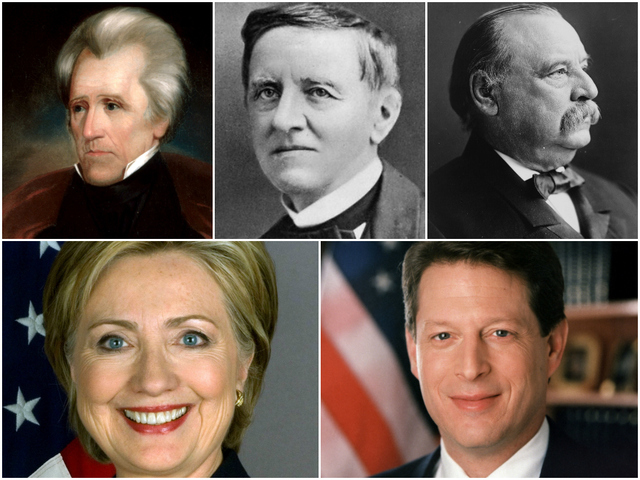

The five losing winners in clockwise order starting top left: Jackson, Tilden, Cleveland, Gore, Clinton (Source: NBC)

The five losing winners in clockwise order starting top left: Jackson, Tilden, Cleveland, Gore, Clinton (Source: NBC)

Under the country’s voting system, known as the Electoral College, voters do not directly vote for a president. Instead, each state is given a certain number of Electoral College ‘votes’, from 3 in sparsely-populated states such as Wyoming and Montana up to a mammoth 55 in California, with a total of 538 votes to be won.

Yet in all but two states (Maine and Nebraska, if anyone’s interested) these votes are won on a winner-takes-all basis, meaning that if you win fewer votes than your main rival in a specific state, no matter how close it is, you end up leaving that state with a big fat zero to your name. What this can mean, as Donald Trump showed in 2016, is that if your wins in key states come at fine margins, while in the states you lose, you lose heavily, you can win millions of votes less than your opponent and still take the presidency.

The Electoral College is certainly a divisive system, particularly in the context of the results of recent elections. One man can’t even make up his own mind about whether it is a “disaster for a democracy” or “genius”.

The electoral college is a disaster for a democracy.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 7, 2012

The Electoral College is actually genius in that it brings all states, including the smaller ones, into play. Campaigning is much different!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 15, 2016

To a lot of Americans, and even more non-Americans, the idea of winning more votes than anyone else but still not winning the election seems patently ridiculous, since the whole point of an election is to let voters choose who wins. How can the winner not win? The unusual logic of the USA’s Electoral College system can rarely be seen in other walks of life: if England score more goals in a World Cup match than the team they are playing against, they are the winners of that match (unless the Russian government decides to tinker with the result – maybe it’s not so different from American elections after all…).

Now this objection to the Electoral College has taken on a legal basis, with a coalition taking four states (Massachusetts, California, South Carolina and Texas) to court over their winner-takes-all systems. The justification for these challenges is that the voting system denies Americans their constitutional rights of being equally represented, with some votes counting for more than others. For example, voters in a swing state with lots of electoral college votes have a much greater chance of influencing who gets to be president than voters in a tiny state which always votes for the same party.

For many, the main defence of the system is the argument that the country should not tamper with something designed by the Founding Fathers. The most obvious retort to this is that if everyone had stayed completely faithful to the Founding Fathers slavery would still be permitted, women would not have the vote, and near anyone would be allowed to carry guns around as they pleased (okay, bad example).

The Founding Fathers, designers of the USA’s unusual voting system (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Founding Fathers, designers of the USA’s unusual voting system (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Perhaps that is a bit unfair. The Founding Fathers’ original motivation for their voting system is understandable. In trying to build a stable political system, they needed to ensure the rights and independence of individual states were not trampled under a ‘tyranny of the majority’, instead allowing states to choose their leaders together. The problem is that their intentions have long been made redundant anyway. Under the original Electoral College, voters did not even vote on the president at all. Instead, they chose wise people representing their state to choose the president for them. But then pesky democracy came along and made sure these wise electors voted for the president they had been expressly instructed to by their voters. The electors now seem like a slightly pointless middleman, while even if states’ rights as a whole are protected they are at the expense of individuals who don’t back the winner in those states.

There is also the potential for things to go very wrong with the system depending on certain outcomes. For example, what if a genuinely popular and influential third-party candidate (not you, Gary Johnson) came along? Such a candidate winning even a handful of states in a close race could result in deadlock, with nobody getting the 270 College votes needed to win. In such a case, the Senate would decide who wins without any recourse to the will of the people – surely not a satisfying outcome for democracy.

It would be surprising if the legal challenges turn out to be successful. Either way, though, maybe it is time for the USA to abandon its historical anomaly of a voting system.