In February 2011, a slogan appeared on the walls of a school in Daraa, Syria: “Ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam” (“The people want to bring down the regime”). The slogan was one of many written on the school wall by a group of teenagers. This act of civil disobedience led to arrests and torture of schoolchildren in Daraa. Protests followed, calling for the release of the boys, which led to a deadly cycle of violence between police and protesters. President of Syria, Bashar al-Assad responded swiftly to the skirmishes with military force, and by April 2011, Daraa was under full government control once again.

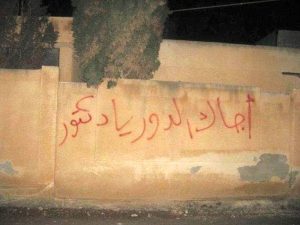

“It’s your turn, doctor.” One example of the graffiti scrawled by schoolchildren, which sparked the first arrests

These words were to lead to a war that has led to the internal displacement of 6.1 million people (within the country) and create 5.6 million refugees. The war so far has left 1.5 million people with permanent disabilities and led to 350,000 deaths, in what has been described by Amnesty International as the worst humanitarian crisis of our time.

“the worst humanitarian crisis of our time” (Amnesty International)

The Arab Spring

The words themselves carried special meaning in the middle-east. They were the words of revolution: the chant first used in mass demonstrations in Tunisia in December 2010. The demonstrations started in Tunisia after a young man, Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after he had been forced to stop selling vegetables by officials. This was the beginning of what has since been termed the ‘Arab Spring’. The Arab Spring started in Tunisia, but the spark of unrest which led to the fall of the president and first democratic elections in the country inflamed revolutionaries all over the middle-east to follow suit. Tunisia was followed by Egypt, then by Libya, Yemen and eventually Syria.

“Ash-shab yurid isqat an-nizam” (“The people want to bring down the regime”)

The conflict in Syria has been in the media countless times since then and has been in the headlines most recently as the unsurprising flashpoint between Russia and America (and by association, their various allies on either side). The original revolutionary protests made by the teenagers in Daraa has spiralled into a proxy civil war between Russia and the USA and the emergence of several new global threats including ISIS. The region is now a kaleidoscope of enemy factions fighting for control daily.

Background to the conflict

In order to understand the original grievances of the teenagers of Daraa, one needs to understand the modern history of the state of Syria. In short:

1946: Syria achieved independence.

1964: The Ba’ath party seizes control of Syria in a Coup D’etat.

1970: General Hafez al- Assad seizes power, dubbing himself prime-minister and one year later President.

Ex-President Hafez-al Assad

During his time in office, Hafez- al Assad (Bashar al-Assad’s father) introduced a number of policies that funnelled wealth to powerful bureaucrats, the military and business connected to people in his government. His family were given positions of power and he gave himself the power to veto all government decisions. He also made sure multi-party elections could not take place- establishing and cementing his dictatorship.

If all of this were not reason enough for civil unrest, Hafez- al Assad was a member of a minority “Alawite” sect of Shia Islam and he ensured the Alawite community were given important government, military and state intelligence positions. This policy greatly angered those within the other (majority) sectarian communities: primarily the majority Sunni- Arabs.

Ethnic make-up of Syria:

Sunni Arabs: 65%

Kurds (non-arab) Sunnis: 8%

Alawite sect of Shia Islam: 13%

Christian: 10%

Druze and Turkmen: 3.2%

Enter Bashar Al-Assad in 2000: Hafez Al-Assad’s chosen successor after his death on 10 June 2000. The politically naïve Bashar was not his father’s first choice, however. First choice, Rifat Al-Assad (Hafez’s brother) attempted to seize control at the first sign of trouble and so was exiled when Hafez regained his health. Bashar’s older brother, Bassel was the next choice, but died in a car accident in 1994, and so, despite criticism from his allies, Hafez groomed his younger son Bashar for the presidency.

The hugely unpopular, Bashar al-Assad, successor to Hafez

Bashar, early in his presidency seemed to be more open to democracy than his father: allowing a free press to start to develop, giving amnesty to political prisoners and even allowing human rights organisations to come into being. But all signs of progress halted within a year and for the next ten years, Bashar ruled in his father’s style.

Since 1963, Syrians had lived under martial law, at the time of the Daraa protests, the education system was crumbling, infrastructure was poor and corruption was rife. Unemployment was intolerably high at 30%. Syria was a powder keg ready to explode; all that was needed was the spark of the Arab Spring. What followed after the Daraa protest was the beginning of one of the bloodiest civil wars in recent history:

A potted timeline of events following the Daraa protests:

[vtimeline id=”3869″]