As Boris Johnson works to shape a post-Brexit Britain, we ask, what could our new trade deal look like?

Post-Brexit talks have commenced and UK Prime minister Boris Johnson has continued to shake political tables this week, after declaring there was “no need” for the UK to simply accept alignment with EU rules in any Brexit trade deal. His statement resulted in the pound falling by more than 1.3%.

In a speech this week, Johnson has called for a “Canada-style” free trade deal – Canada’s current deal with the EU came into force in 2017 and is called the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). Although it has not been signed off by all of the EU member states, CETA will, according to the European Commission, “lower customs tariffs and other barriers to trade between the EU and Canada,” and “uphold Europe’s high standards in areas like food safety, worker’s rights and the environment.”

Michel Barnier stated the EU was ready to offer a “highly ambitious trade deal”, which included zero tariffs and zero quotas. But, he said, this was dependent on the UK agreeing to “specific and effective guarantees to ensure a level playing field”, meaning compliance with EU rules and checks.

CETA, according to the BBC, removes most of the tariffs (tax on imported goods) between the EU and Canada and it also increases quotas (the amount of a product that can be exported without extra charges). However, it does not seem to influence trade within services or financial services such as banking – and these areas are important for the UK currently, yet alone the future.

There have also been concerns over American products coming to the UK as part of a proposed trade with between the UK and the US. This is because of criticisms of American food, hygiene standards and animal welfare. In a recent speech during which he stated his goals for post-Brexit trade, Johnson reportedly said that the UK would be “governed by science, not mumbo-jumbo” and he criticised “America bashers” with a “hysterical” attitude towards American food and view it as “inferior.”

However, Johnson has acknowledged the arguments against chlorinated chicken for example, which is sold in the USA. As reported by The Guardian late last year, some experts have warned that the government have “misunderstood” the science aspect of the safety of chlorinated chicken. Erik Millstone, professor of science policy at Sussex University, said: “I am satisfied [by the evidence] that US food poisoning cases are significantly higher than in the UK. A minority of people suffer fatal complications. There will certainly be fatalities, and they typically affect vulnerable people, such as infants, small children and the elderly.”

If Millstone is indeed correct, this could put an incredible strain on UK services such as the NHS. The question is, is Johnson ready to sacrifice the integrity of goods and services to save or boost the British economy?

Brussels has threatened to place tariffs on UK goods unless he complies, by government officials such as Chief Secretary to the Treasury Rishi Sunak, have said that “trade is only one part of what’s going to drive our economy forward” and that “we want to have a free trade agreement…but that does not mean we should have to follow all their rules, that’s not what free trade agreements typically involve – it should not be the case here.”

Johnson has set a very strident tone going into these negotiations, positioning Britain on the cusp of supposedly global opportunities. Raab echoing his sentiments in the commons, saying it was time to “look ahead with confidence and ambition”. The central problem still remains; moving forward with the best economic interests of the country at heart means sacrificing the ideological idea of breaking away from the European model that so many Brexit voters and of course hard-line Brexiteer politicians champion. The other key difference is between the “goods” and “services” areas of trade deals. The Canada deal gets rid of tariffs (taxes) on the majority of goods traded between the countries – some “sensitive” food items, including eggs and chicken, are not covered by it. However services like banking, which make up 80% of the UK economy, are crucially not really a part of this kind of agreement.

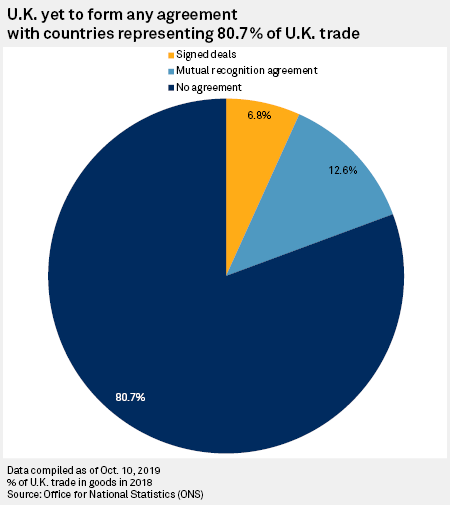

Talks are due to begin in earnest in March. For now the UK remains under EU rules for the rest of the transition period, due to end in December. With the EU making up over half UK total trade in goods in 2018, there is no doubt that future trade deals struck with the bloc will be consequential. Since the Brexit vote in 2016, the Department for International Trade has to date secured trade agreements with countries that cover just 6.8% of total U.K. trade in goods, according to calculations by S&P Global Market Intelligence. There is no doubt that the road that Britain has chosen to take is a difficult one, and whilst there will be many other factors in how Britain is shaped, trade will have a deeply profound effect on most areas in the lives of Britons.