On the 6th August 2020 at 6.07 pm local time, the central district of Lebanon’s capital Beirut was struck by a gargantuan explosion. The blast caused over 135 deaths, 5000 casualties and was felt as far as 240 kilometres away in Cyprus – registering as a 3.3 magnitude earthquake. The tragedy has caused many to reflect on the country’s colonial past. We take a look at why equating Beirut to ‘Paris’, a city that has its own prevalent global influence, repackages a culturally lavish Arab nation into a more palatable western alternative.

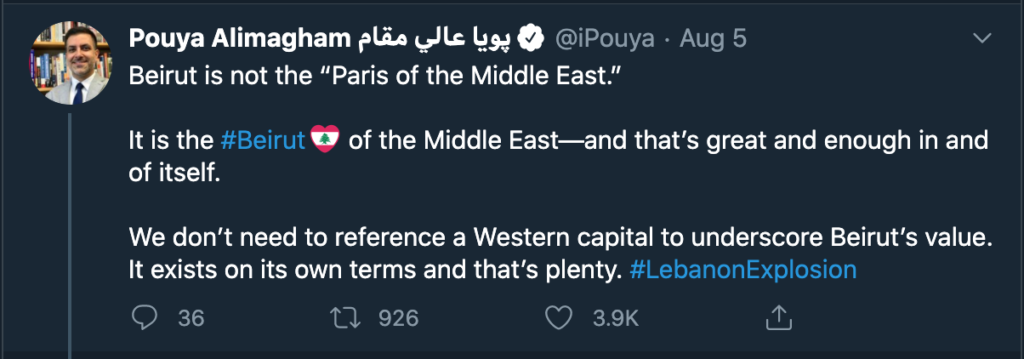

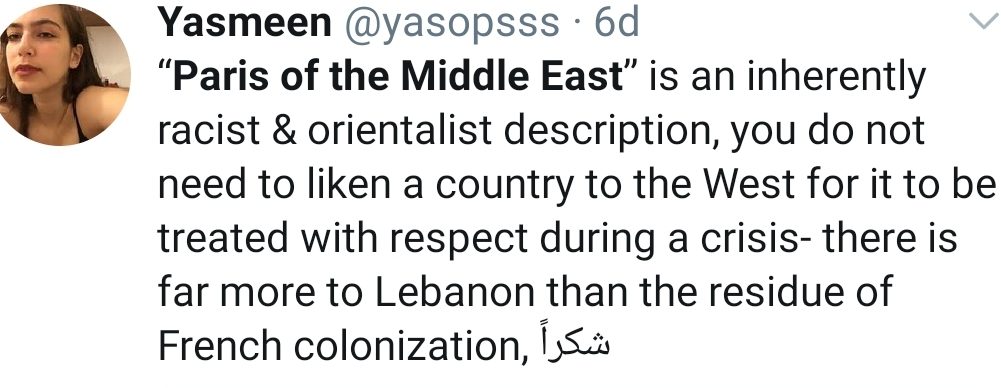

Amid the critical discourse surrounding the incompetency and failures of Lebanon’s now former government, public responses to the Beirut disaster have also been under fire. In particular, the country being referred to as the ‘Paris of the Middle East’, has engendered extensive backlash from those who claim the statement is oversimplifying, reminiscent of colonial influence and supercilious in nature.

Before expounding on why this controversial analogy is causing unrest on social media, understanding where the comparison stems from is essential to grasping the crux of the wider debate.

One of the reasons why Lebanon is often compared to Paris is because of France’s mandate over the land from 1920 until the creation of the National Pact in 1943. After the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement post World War I, Great Britain and France secretly demarcated their respective spheres of influence within the Arab lands formerly residing under Ottoman rule. Throughout the mandate, the French reformed education, public utilities and communication, however subsequent mismanagement and the influence of the Great Depression saw the Lebanese agriculture industry plunge into decline and the silk business begin to crumble.

Lebanon is also likened to Paris due to the cultural parallels between the two lands. As a result of being so widely romanticised in mainstream entertainment, books, social media, fashion and art, Parisian culture has become somewhat synonymous with beauty and allure. In the same vein, Lebanon has distinguished itself as a distinct and dynamic location. The charm of its culturally rich Arab heritage in conjunction with comparatively liberal social norms, has linked it to the capital of its former colonisers.

Oversimplifying?

But why is this such a contentious statement? For many, this is an oversimplification of Lebanon’s cultural legacy and diminishes its innate reputation as one of the most unique countries in the Middle East. Equating Lebanon to ‘Paris’, a city that has its own prevalent global influence, repackages a culturally lavish Arab nation into a more palatable western alternative. It can further be argued that this oversimplification is a means to fill a vast void of knowledge in the West. Reconfiguring Lebanon’s geopolitical identity to fit the expectations of a swathe of less informed Westerners is, in essence, eroding the country’s ‘sense of self.’

Reminiscent of colonial influence?

To add to this erasure of ‘sense of self’, associating Lebanon with its former colonisers can also be considered reminiscent of the imperial forces that governed the land in 1920. Alluding to Lebanon as the ‘Paris of the Middle East’ undermines the independence it gained in 1943. After the French departed, the National Pact divided Lebanon’s governing system along sectarian lines and endowed corresponding executive influence upon all of its religious minorities (including Catholic, Orthodox and Maronite Christians, Shia and Suni Muslims, and the Druze and Jews). The pact delineated that the President of the nation would always be a Maronite Christian, the Prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of Parliament a Shia Muslim. Seats in Parliament were also set to a ratio of 6 to 5 in favour of the Christians who made up the majority of the population at the time.

However, the proportionate representation of each religious demographic in the country has arguably formed the fault lines for the current political disarray. The segmented system is replete with corruption and has resulted in parliamentary deadlock, causing resentment amongst many Lebanese people who view the institutionalised divisions as the instrument of their downfall.

As civilians grow tired of the archaic systems that govern them, a more favourable outlook towards the French begins to develop. This may be a consequence of intense frustration regarding the local government’s defunct efforts to improve standards of living, or perhaps due to an internalised imperialism that exists within many previously colonised nations.

Condescending?

Lastly, referring to Lebanon as the ‘Paris of the Middle East’ can be considered problematic when contextualising the crisis as a whole. Drawing comparisons between what Lebanon used to be, and what it is now by affixing it to a European capital insinuates that it is only deserving of sympathy as it is imbued with significant European influences and thus does not conform to the ‘war-torn’ stereotype people associate with other typical Middle Eastern countries.

Despite how the narratives surrounding the explosion have been framed, Lebanon is likely to descend further into economic decline as the main port was destroyed in the blast. Inevitably, this will cause a country that is largely dependent on imports to experience extreme food shortages in the near future, causing a surge of growing concern and anger.

An impending economic collapse, therefore, solicits further debate regarding how justified the influence of the French will be in providing humanitarian aid and financial support. Trenchant opinions and attitudes towards the tragedy on social media also beckon the question, is Lebanon valued because it is unlike other stereotypical Middle Eastern countries? As the discussion carries on, social media users continue to condemn associations with Paris and aim to spread awareness about the country’s individual identity.