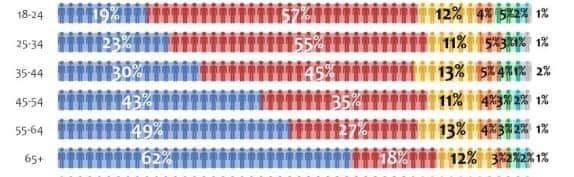

Last weeks Election results showed a clear divide between young and old in the UK voting choices. 57% of 18-24-year-olds backed Labour while only 18% of the over-65s.

Labour’s election bid was one of hope. They appealed to the idealistic youth and made promises to deliver a functioning, modern socialist Britain. However, the ‘Youthquake’ failed to emerge from social media echo chambers and adequately engage the intergenerational segregation. This failing was not the Labour Party’s alone, but from a wider lack of understanding from the young to the old:

“You were us. You have forgotten what it was like to be us.”

The intergenerational sharp contrast was brought to the fore with Thursday’s General Election, with the #OkBoomer trend at the forefront of shunning the older generations for dismissing the agency or challenges faced by young people today.

A Manifesto of Hope and Equality

The Labour manifesto pledged to address student debt, the housing crisis, low pay, lack of secure skilled work, childcare, mediocre yet expensive public transport, education budget cuts and the pressing climate emergency.

These are the perceived pressing issues for younger generations. They reveal a tale of disaffected youth, locked out of their country’s future.

Perhaps the fact that their ambitious idealism is wasted when the wealth they help create ends up in offshore accounts helps explain why Corbyn’s “equality” and “inclusivity” garner such support from a generation whose living standards have been systematically assaulted.

Labour’s Social Media Campaign

Jeremy Corbyn’s digital strategy centred around making persuasive viral content – bypassing the “Murdoch” media and breaking out of the bubble.

On Facebook, Jeremy Corbyn and Labour achieved 86.2 million views on campaign videos, compared with only 24.5 million views for Boris Johnson and the Conservatives.

Giles Kenningham, former director of communications for the Conservative Part, said: “Labour has used Momentum to devastating effect. The Tories do not have an equivalent campaigning group pushing out their message.”

If you spent enough time on the Twittersphere or various other social media outlets receiving both zealous support from students and the wall-to-wall Labour Party sponsored coverage, you may have found the overall election results rather a surprise.

‘Youthquake‘

The “youthquake” first coined in 2017 failed to materialise as tangible election gains for the Labour Party. This was a theory that mass engagement of young voters would swing the balance in the elections.

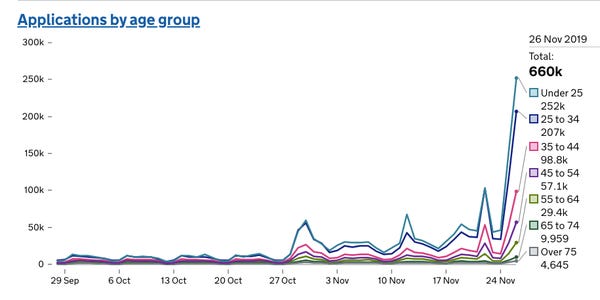

Left-wing academics and Labour strategists will be scratching their heads as 67% of the 3 million who applied to vote since the election were called were made by people under 34 years old. This age group tends to be more likely to back Labour over Tory.

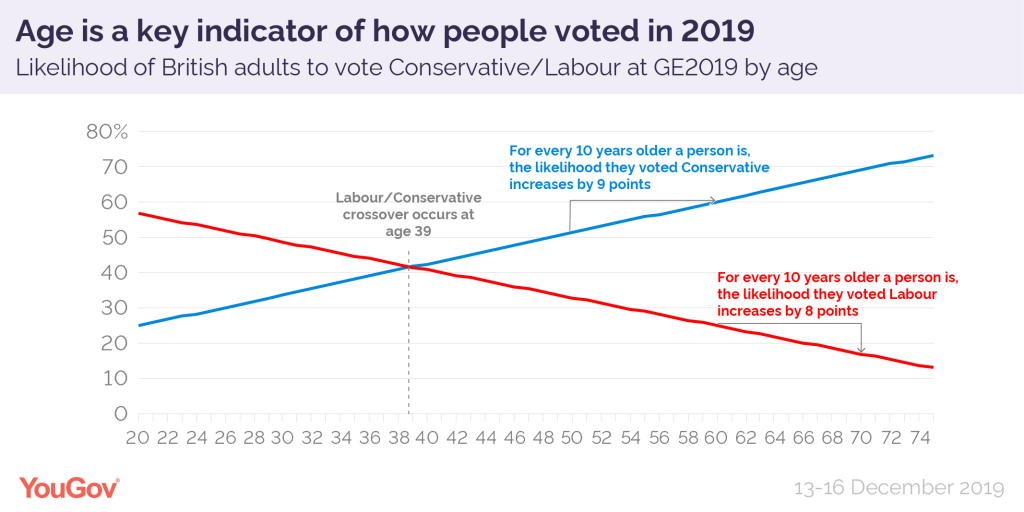

56% of 18 to 24-year-olds voted Labour in last week’s election, but this dramatically falls to just 14% for voters aged over 70. The average age of conversion Labour to Tory now sits at 39, down from 47 years old in 2017’s General Election.

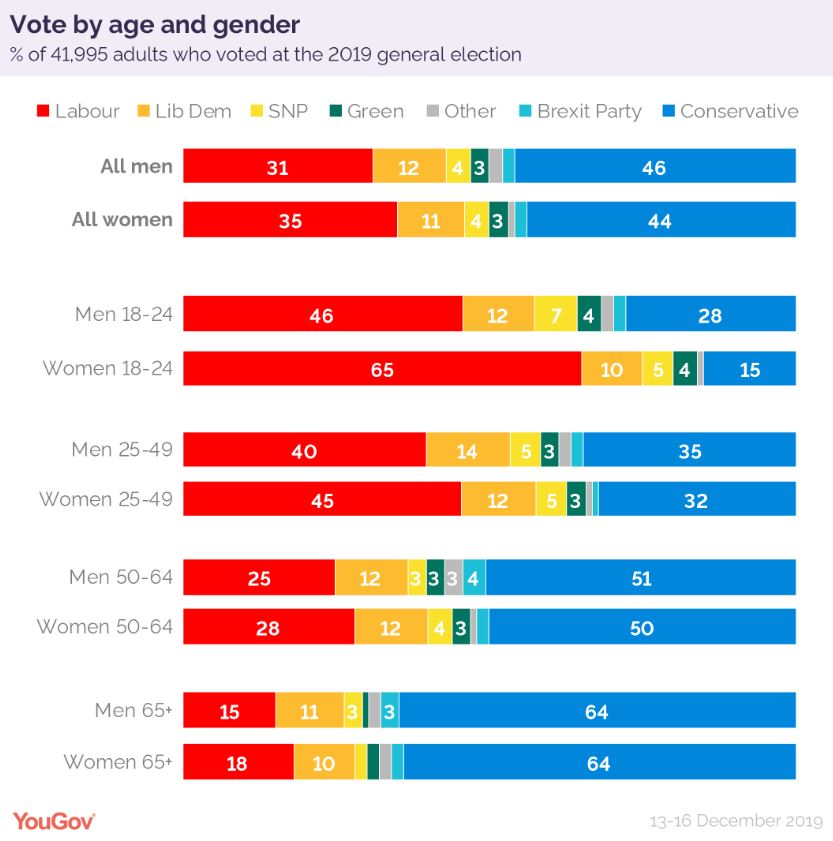

The most noticeable age gap was in the youngest category (18 to 24) where 65% of women voted Labour compared to 46% of men.

The surge to register to vote was driven by calls on social media from multiple celebrities, with rapper Stormzy and Game of Thrones actor Emilia Clarke were two such high profile figures appealing to their young fans. A total 660,000 last-minute applications were made.

Voter registration has also been driven by Labour activists’ face-to-face drive to sign up voters at colleges, universities, mosques, churches and job centres.

2017 vs 2019 Youth Engagement

Patrick Sturgis and Dr Will Jennings, University of Southampton, made a study of the 2017 election showing Labour did inspire more young people to vote than had previously been acknowledged. Of the 40,000 households surveyed, 2017 versus 2015 turnout among the youngest voters was substantially higher, and further still than 2010.

Lower visibility may account for the disbelief on social media as the Exit Polls were announced. This shock shows how echo chambers or filter bubbles feed cognitive dissonance. This is the psychological stress that emerges when contradictory beliefs clash, and the brain struggling to make heads or tails out of the situation to reduce the discomfort and restore balance. In this case, Labour supporters appeared significantly more vocal than “shy Tories” who are less likely to tell opinion pollsters who they were voting for. This bolstered their confidence by constant reassurance feedback from other members possessing similar viewpoints (namely other Labour supporters).

Demographic of a Conservative Voter

As Conservative voters tend to be older, they are less likely to be social media users in the first place, and those that use Facebook do not air their opinions, on balance, as younger idealistic users.

The big online story during the 2017 general election was the influence of a huge network of pro-Labour websites, accounts and groups.

But changes to Facebook’s algorithm – the code determining which posts get seen – have made it much harder for these sites to reach massive numbers of people.

And this time Jeremy Corbyn’s online cheerleaders had more competition from popular pro-Brexit groups. Throughout the campaign, and particularly after the Brexit Party announced they would be standing down in Conservative-held seats, the chatter in those groups swung steadily in favour of Boris Johnson.

Most Successful Media Campaign Ever Seen

A Labour press release the day before the election claimed that the party ran “the most successful election social media campaign the country has ever seen”.

That may have been the case. Most of the top viral videos were pro-Labour. But that doesn’t seem to have translated into more votes.

Social media users are not necessarily representative of the UK. Research by Pew suggests that users of Twitter, and to a lesser extent Facebook, skew young, left, and pro-EU, while older voters – who are more likely to vote Conservative – are less likely to be active on social media.

There will be more analysis in the coming days, but it’s clear that we have yet another reason to look below the surface when it comes to politics online.

Infinite pledges made voters distrustful Corbyn’s sincerity or integrity

The Labour manifesto seemed like it was saying everything and anything to convince people to vote labour rather than actually setting out a clear and comprehensible strategy for government.

From the free government WiFi to free tuition fees that seem to cater more towards bribing the youth vote than actually running the country, it isn’t hard to see why this was met with a healthy dose of aged scepticism. In fact, Labour almost exclusively courted the youth vote and neglected anyone over 30 living outside London

Older generations have paid tax all their lives. When they approach retirement, the direction of that cash flow can reverse. They don’t want to see the entitled youth of today take all their hard-earned money and fritter it away on fancies exclusively targeted at the young.

The older generations saw right through the bombardment of flaky promises by Labour every time they looked like they were slipping in the polls. They have lived through countless expedient political careers to know better. And this catering to a certain audience by Labour marks a clear social discord between young and old in Britain today.

Everyone suffers from the segregation of the old and young

Older people bring a sense of the big picture, stories and experiences to those younger than themselves. Young people keep their elders in touch with new ideas and a changing world. Both give each other a broader understanding of life and the things we all have in common.

In Europe, the number of people over 65 already exceeds those under 15. As Britain ages, the young are more than ever not privy to the wisdom of their elders; and the older generations aren’t shown the brave new world.

By reconsidering the nature of the intergenerational contract as a means for growth and learning, rather than one of obligation, we can create a whole new world of opportunities for everyone.

#OKBoomer Age Bashing

Youth bashing isn’t the exclusive province of older people. Young people get into it too, especially those inclined to sentimentality.

Millennials are sick of baby boomers telling them what life is like. They get terrible advice like “just go out and get a job”. Young people have entered the job market during the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression into considerably a more competitive working world, demanding higher qualifications and experience dilemmas – you need it to get it. They had to fight to establish themselves.

Ok Boomer is not so much tied to age as it is to people embodying a certain form of cultural logic that tends to speak down or place blame on Gen-Z. It seems to relate to the inability to see past one’s own experiences to engage with those of others who are different. A Peter-Pan-esque mentality toward cultural norms and changing societies. What is sorely lacking from the discussion, if it is had in the first place, is compassion and understanding.

This old chestnut is quite provocative, to say the least. Outright denying the agency and concerns of the young as willful ignorance or naivety.

As if the politics and ideologies on how people should be treated are to be dismissed as poppycock and gobbledegook simply because they haven’t reached the sheer wisdom of one’s fifties. Perhaps if they haven’t altered their view from Labour to Tory by then, the goalposts will shift once more.

Are we a damaged generation?

Gregg Easterbrook wrote in Washington Monthly, condemning the collective youth in a piece titled “Fear of Success.” He accused the era’s twentysomethings of longing for boring and unchallenging jobs, self-sabotaging their romantic relationships, and even refusing to vote for fear of believing in change. This damaged generation, he wrote, “believe[s] it foolish to gamble for accomplishments when accomplishments will cause more to be expected of [them].”

“They have become too distracted by their screens or are slaves to frivolity. Young people don’t speak of their own experience, but rather, they’re speaking in contrast to someone else’s.”

Gregg Easterbrook’s “Fear of Success”

Filth Down From London, Exclusion by Derogatory Acronym

It is this constant comparison and unrealistic expectations of living standards that have given rise to the phenomenon of the “DFLS” – “down from London” or “Filth” – “Failed in London, tried Hastings”. The high cost of living in London has pushed young people out to marginal seats where they have been targeted by Labour’s election campaigning to “turn them red”.

Young people have been raised to expect their life would always get better. They are frustrated by stagnating living standards and prospects that better reflect their reality than those they feel entitled to.

Parents falling out with their kids over voting patterns shows the disdain young have for the older cultural ideologies they feel don’t deserve unchallenged acceptance at face value. The new generations do not play by the rules of “respect your elders” on an automatic basis. They shun blind acceptance of ideals and critiques solely based on your age, an approach no better than the identity politics Boomers constantly whine about. You are not who you are to everyone, and blanket respect is considered meaningless. Trust needs to be earned in 2019, it isn’t given unconditionally.

Full Circle

Labour’s overdependence on winning over the 18-35 voters may have contributed to the Tory landslide for both the failure of the young and their campaign teams to appreciate the British electoral fold.

Their strategies misjudged the turnout of old versus young because of the exceedingly different cultural ideologies at play as society drifts further and further apart with each generation.

The Electoral Commission says only 71% of 18-34-year-olds are correctly registered. While Corbyn seems authentic and genuine to this age demographic, the Brexit issue and other manifesto contradictions made him appear instead of acting on principle, he was just doing anything to get elected. Desperation is easy to sense, and regardless of your walk of life – dating to sales – is rarely appealing.

Common Sense Perspective

The reasons for the abysmal performance may be attributable to many different factors in British society that a youth turnout couldn’t overcome. From the dissipated enthusiasm since 2017 where Theresa May’s U-Turn on Social Care was easy to attack as a “dementia tax” and people rallied around their new Tribune Jeremy Corbyn’s Momentum movement for real change. Or the consistency in turnout between young voters as the British

Election Study supposing 40-50% 2017 was consistent with 2019 and 2015, showing the engagement was more media fluff. Or maybe it was Boris Johnson gave little meat on the bone to pick for Labour, eschewing TV debates and the interview with Andrew O’Neill.

Others have pointed toward Labour abandoning its traditional voting base of the working class or discontented populations up and down Britain in favour of Extinction Rebellion young idealists, creating a contradiction they cannot surmount. Maybe the best explanation is this wasn’t really a general election at all. Maybe it was a confirmatory referendum in disguise. Britain, a people fed up with dillydallying around, making them a laughing stock of the global community, voted on their feet to demand a resolution with the only viable candidate they saw.