by Benedicta Denteh

It has been almost a year since we all had the absolute pleasure in watching the movie that is considered a breakthrough blockbuster with regards to black representation in Hollywood. Marvel’s Black Panther had us all tingling with pure pride and joy, having been the first time many black people could see themselves on the big screen being represented in a positive light. Finally! Although there were many scenes which sparked our interest and caused us to reflect on our own lives there was one scene, right at the beginning, that was far too familiar.

Erik Killmonger, played by the incredibly devoted actor Michael B. Jordan, is walking around the Museum of Great Britain admiring the West African exhibit and its artworks.

“How’d you think your ancestors got these? You think they paid a fair price? Or did they take it like they took everything else” Killmonger says directing an intimidating stare at the department specialist.

He knew he was right. For a villain, Killmonger had us all unequivocally rooting for him as he took control of West African goods. We understand him and his cause. All the artefacts there, or at least most of them, seemed to have been unrightfully owned by the British Museum or at least acquired under questionable circumstances. While most of us moved onto the next scene it begs the question. How many African colonial artefacts in this day and age does the UK currently hold in its possession? What exactly do this country have? And the biggest question of them all, will they ever be returned?

One of the most unlikely advocates of this interrogation is Emmanuel Macron. In the winter of 2018 Emmanuel Macron, the current President of France, pledged that during his office, he would return the African Artefacts that are currently under French possession. These artefacts sit under strict laws of patrimony which deem them as French property. Macron pledged to make this “one of {his} priorities” due to the fact that while there is historical explanation for the possessions being there, there are no fully valid justifications for them to still be under French ownership. In 2019 he has vowed to return thousands of items and now African countries, in particular Benin, is waiting in anticipation of the return of around 3,000 items.

This has since inevitably brought forward a debate on whether other European countries will follow suit and begin to discuss whether to loan or return historical artefacts back to their rightful owners. According to several reports 90% of African cultural heritage resides in Europe, mostly in the UK and France, evidently due to the colonial history, but also Belgium and Germany.

Should Colonial Lootings Be Returned to Africa?

My initial response was absolutely! Surely it’s simple. The items were stolen and so they must be returned. Done. However, upon more research I realised that perhaps the whole process would not be that easy.

Morality

“When someone’s stolen your soul, it’s very difficult to survive as a people” ~Prince Kum’a Ndumbe III of the Dula people in Cameroon

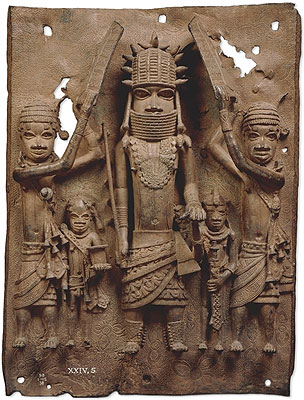

As Prince Ndumbe III explains above, the obtaining of any art works or prized possessions of another’s community, no matter how small it is, attacks the heart of a society. A people’s history is integral to culture and the building of their own identities. So when the physical cultural heritage was removed (through military seizures, armed battles and/or swindling etc.) part of the people are taken too. I couldn’t imagine the devastation if the same happened here in the UK but with the crown jewels instead of Asante Gold and Benin Bronze.

Many countries have been asking for their items to be restored, and some are ready to get them back with the opening of The Museum of Black Civilisations in Dakar, Senegal in December 2018 which debuted under Léopold Sédar Senghor Senegal’s first President. His vision was to create a museum that would represent combined black history and contemporary cultures of black people all round the world. The opening of a new museum in Edo State, Nigeria in 2021 awaits the return of many art pieces.

But that brings in to question the practicality of it all when we stretch the idea of returning products to their rightful owners.

Practicality

Some of the products that the west currently possess are old, and I mean really old. This doesn’t excuse not returning the items, but it does mean that the transportation and condition of them must be taken into consideration. These old artworks, require museums and exhibitions in top condition and the correct preservation tools and equipment to ensure the preservation of these objects of art. Unfortunately, as it stands some places (outside of the UK) may not be ready to be the home of such valuable creations.

In addition to this, there’s a long process in finding out exactly where everything belongs. Africa has reshaped many times and therefore something that was once owned by a Beninese community ethnic group (or tribe), for example, may now be a part of modern day Nigeria. Not only will there be long debates on where exactly they belong but also who they will go to, if they will be returned on part-time or permanent loan etc.

Another question is whether there is a need for the artefacts to be put back exactly where they were stolen from or whether there’s just a need to know where they are and have unlimited access to them.

What is happening right now?

Everything is now a matter of putting words to power. Law changes will be required, on-going discussions and an international conference planned by Macron about the return of African Artefacts this year will be taking place to decide the future of African Cultural Heritage in Europe. From there, other artefacts, from many other countries, which have been taken such as the Hoa Hakananai’a stauteof Easter Island will be pulled under heated discussion. It has been the object of decades of dispute between the inhabitants of the Polynesian island and the British Museum and this year we may see plans of the restoration of the culturally integral sculpture.

The matter of fact is that countries in Africa, and many other countries, have been cheated out of resources, their lives, land and goods for hundreds of years. The least that the west could do is return some of the artefacts which were unrightfully stolen back to their homelands.

But would this come at an expensive price?

Benedicta is currently studying Arabic and French at the University of Manchester and hopes to become a linguist and broadcast journalist in the future. In her free time, she enjoys learning about African development and issues to do with race and culture. Benedicta also takes pleasure in acting, travelling and promoting plant-based eating.