The supply shock is allowing companies like Amazon’s sellers to engage in price gouging. This comes as the largest stimulus ever was passed by Congress. When Covid-19 ends, we will have lots of excess money in the system without as many products as before the pandemic. All those companies that closed up shop for good, or don’t have working capital to ramp up operations will leave more money chasing fewer goods. Add in very cheap business and consumer loans from a well capitalised banking system from numerous sets of Quantitative Easing (QE) and now 0% central bank rates, we are in for trouble.

Way back when

The Federal Reserve has created so much money that prices are going up. It didn’t happen during previous money printing rounds because financial institutions weren’t well capitalised. We didn’t have a broad supply side shock like the Covid-19 crisis and there isn’t the benefit of downward pressure on prices that Chinese cheap labour afforded us.

Financial crises have been followed by inflation trajectories tied to monetary policy and money creation by the banking sector during those crises, but supply side interactions with the evolution of broad money aggregates in response to those crises explain why Argentina’s financial crisis in the early 2000s was followed by increasing inflation. Meanwhile Japan lived through a ‘lost decade’ of deflation 1991 to 2001 despite QE.

Stagflation

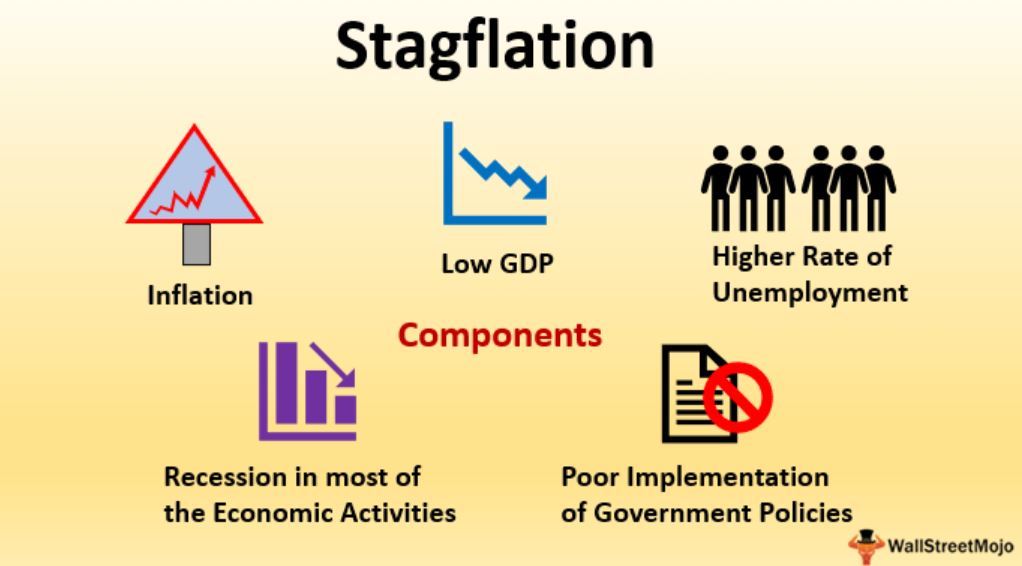

What we end up with is stagflation. This is when inflation and unemployment are high, but economic growth is low. This happens when central banks expand the money supply at the same time as supply is constrained.

If the government were serious about tackling the upcoming problems that they created, they need to raise interest rates, thus making money less accessible. People will need to take the pain, but at least their purchasing power would go further. Right now, our governments are wiping out the purchasing power of lifelong savers.

Peter Schiff tweeted this week on money supply and FED balance sheet:

“The Fed’s balance sheet exploded by $557.3 billion in the last week to $5.812 trillion. More shocking, money supply surged by $436.1 billion. In the past two weeks, the Fed’s balance sheet is up by $1,143.4 trillion, fourteen months of QE3, and money supply is up $606.2 billion.”

Perfect Storm

A health crisis preventing people working, making them ill and disrupting supply chains is a large shock to productivity, similar to an oil price shock or a natural disaster. The limited supply of labour and production will mean more money is chasing fewer goods, leading to inflationary pressures. The cancellation of the tourism industry globally, which accounted for 10% of World GDP before the crisis, alongside closing businesses, restaurants, shopping centers, cinemas and health clubs has created a large negative demand shock.

The combination of both shocks will rapidly increase the unemployment rate and trigger a large economic recession. However, the decline of both demand and supply means that we should not expect to see the falling prices and deflation that occurred during the Great Recession and Great Depression.

In the short run, emergency lending programs will add the liquidity needed to keep credit markets functioning, and the proposed tax rebates will help individuals and businesses weather the storm. While both of these policies will keep demand from collapsing. Consumers propped up by lending programs, return to spend and borrowing at historically low rates.

Prolonged closure of business and supply chains will create further shortages throughout the wider economy, not just nitrile gloves, disinfectants and face masks. Lower investment restricts future potential output. The money supply growing faster than growth in real output means more money chasing fewer goods. Companies like Amazon, in responding to the increase in monetary demand, put up prices to better reflect the scarcity allowing the price mechanism to effectively clear the backlog. This comes at a cost of inflation, which reduces purchasing power of consumers and harms savers who don’t own assets growing faster than the prevailing rate of overall price increases.

Trouble is, lowering interest rates in response to such a health-related event will not put infected individuals back to work. Firms, still anchored to the old level of wages, won’t realise the market has moved. As a result, they leave vacant job positions unfilled, holding out for a better candidate and not realising that the rules have changed, and you will have to pay up to get someone good.

Michael Woodford’s view in his 2003 ‘Inflation Targeting and Optimal Monetary Policy’ paper is that central banks can just raise rates when inflation arrives.

Sadly, it isn’t that easy in practice, as we painfully found out in the 1970s. The lag between excess monetary growth (the increase in money supply over potential output, adjusting for the influence of interest rates on the demand for money) and inflation is substantial. Across all economies its around 40 months, and for developed economies its even longer.

Concerns about inflation seem utterly misguided – ‘since it hasn’t happened yet, it won’t happen’. These opinions get caught up in the noise of ‘these shortages are as temporary as the supply chain bottlenecks and so too are the price increases’.

As the worst point of the crisis passes (while the labour market lags economic activity), the market clearing level of wages (‘shadow wages’) remains below the current actual level but slowly creeps up over time.

Once shadow wages surpass the current actual level, things can take a dramatic shift, and the rate of increase that was once hidden (not observable) starts to manifest in actual observed wages.

Only this time we don’t have competitively, lower priced Chinese unit labour costs. But we do have a progressively aging demographic.

When the ice cube starts to melt, it starts slowly, but when you begin to notice it, suddenly it ‘appears’ to speed up. The same is true with wage price increases and wider inflation. We all get blindsided because we were so distracted from what really matters while caught up in the daily noise.

All this comes with a political environment with a President who called for zero interest rates in a fully employed economy amid a weary public audience tentatively emerging from recession. The FED has been trying to rediscover inflation since 2008, Covid-19 may prove the answer, albeit an overdose.