The first viable vaccine rollouts will be in 2021, unless you’re considering Putin’s special Sputnik V soup. After all, this is a virus we are talking about – and we’re still waiting for that AIDS vaccine 30 years later. Governments were slow to react and lacked the ingenuity to solve this. Universities alone lacked funding and large-scale manufacturing capacity.

Big Pharma is struggling as we found out through the World Health Organisation’ leaked documents about Gilead’s Remdesivir failure to confer protection against Covid-19. Not only did it not work, but it also had serious adverse side effects which would have been known prior to the trials. But that didn’t stop them or Inovio Pharmaceuticals nor the plethora of other biotech firms leading everyone up the garden path to jack up their share prices and receive large funding budgets.

How epidemics fizzle out

Either everyone who can get infected does, as with Black Death in the Medieval period, or Smallpox in the Age of American Discovery or Spanish Flu 100 years ago. Alternatively, quarantining of the sick prevents further spreading, like with leper colonies. Or as we have seen with Wuhan, China recently or SARS 2002, authorities track and trace the infected, quarantining them to prevent further spreading.

A vaccine or treatment may be found and alleviate the infection by disabling the virus. Given how long medical trials take, and whether long-term antibodies can confer long-term immunity is also in question.

“vaccines have a normal success rate of 7% preclinical, with 15-20% clinical, so we can never guarantee in these circumstances”

Sir Patrick Vallance, Chief Medical Officer, United Kingdom

Germany or England

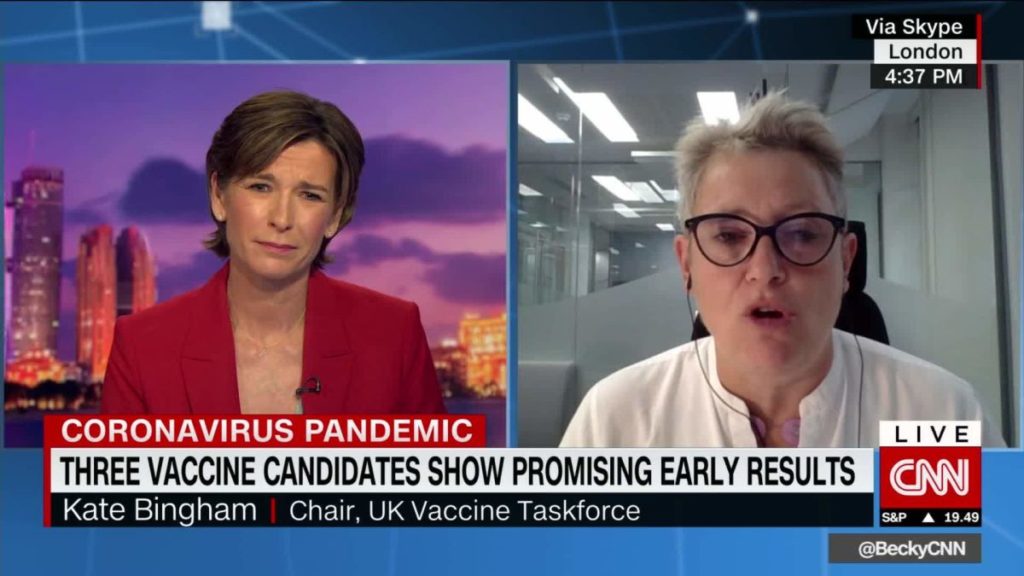

Kate Bingham, chair of the UK Vaccine Taskforce says that “Oxford University or German BioNTech are the most likely candidates to be ready this year.” The British vaccine is most promising because it induced T-cell responses, which may improve further after a second or ‘booster’ jab. Separate studies suggest antibodies may fade away within months while T-cells remain in circulation for years. Unfortunately, Britain’s Chief Medical Officer did warn the UK this week it was unlikely there will be a vaccine before the winter of 2021. Regardless, the world awaits Professor Adrian Hill and his team’s Phase III update this Fall.

In terms of the rollout, the first 30 million doses will go to the UK’s most vulnerable. To scale up production, AstraZeneca’s manufacturing facilities have been preparing the Oxford study’s lead candidate. They also announced a $1.2 billion deal with the US government to produce 400 million doses of the unproven coronavirus vaccine. If the Germans beat us to it, our Government has agreed to secure the Pfizer and BioNTech joint effort vaccine.

In a game of high stakes, we are down to the final hands. If proven effective, the ZD1222 vaccine would allow people to leave their homes, go back to work, and rebuild the economy.

Sir Patrick Vallance, the Government’s chief scientific adviser said the development of an effective vaccine could never be guaranteed, stating “vaccines have a normal success rate of 7% preclinical, with 15-20% clinical, so we can never guarantee in these circumstances.”

It remains unlikely the West will trust the Russians or Chinese vaccines that haven’t undergone the same rigorous safety and efficacy protocols the West adopts. Besides the political postulating to get both international leverage and domestic party-political clout; these manoeuvres are not out of form for such regimes.

While health experts have warned we should expect “multiple waves” of the virus, this has led to cause for concern that mutated strains may nullify our effective prevention options. Fortunately, to date, there haven’t been new viruses emerging which we cannot prevent by the immune responses generated in the current vaccines under development.

In the end, vaccines may never bear the promised fruits, but instead entrepreneurial companies with niche proprietary formulas or delivery mechanisms to prevent airborne infection may prove most effective. What really worked was the social distancing, wearing of masks in public places, washing hands regularly, personal hygiene measures and simple innovations like new nasal inhalers due to launch in September that were initially developed 17 years ago to tackle the first SARS epidemic. Just as these technologies never made it to market the first time, some companies took on the risk to bring their products to market because they saw the potential future need the rest of us did not. Whatever the outcome, we should learn these lessons well this time, because the next pandemic could be a completely different beast altogether.