As jerky valuations on Wall Street signal another week of tanking tech shares, Elon Musk’s eccentric AI endeavours captivate the attention of the world once more. On the 28th of August, Musk’s neurotechnology start-up, Neuralink, demonstrated how it would merge human consciousness with technology by live-testing its most recent prototype on Gertrude – a common farm-bred pig. The dystopian ‘brain implant’ device has prompted concerns that invasive technology will trigger a transcendence into a Black Mirror-inspired reality. Contrary to such outlandish theories, Neuralink technology is unlikely to spark the advent of a Kafkaesque era of life. The technology can, however, prove to be destructive in other ways that may still warrant ample concern.

The Link

The Neuralink device, a brain-machine interface, uses biomimetic decoding to potentially treat neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease. It is also capable of potentially restoring movement in paralysed patients through robotic prosthesis – all controlled by a single 0.9-inch brain chip. Musk’s vision for the technology entails an allegedly ‘non-intrusive’ operation in which the chip’s slender electrodes will be sewn into sensitive brain tissue by an automated surgical robot in a one-hour procedure that causes ‘no noticeable bleeding or neural damage.’

Irrespective of the theoretical benefits Neuralink offers the world’s handicapped population, the prospect of undergoing a chancy computerised operation is terrifying. Not only is the implantation mechanism a source of consternation, but the power to tap into vast amounts of neural data is also a worrying notion. Although it is highly improbable that the technology can harvest thoughts, memories and feelings, Neuralink may alternatively provide access to information connected to the types of stimuli that trigger specific nervous-system responses. Information of this nature has unprecedented value in today’s data driven economy.

The value of data

Data is a sought-after commodity used to train AI algorithms, create targeted advertisements, plan business strategies and much more. Commoditised personal data collection has fuelled the success of many corporate enterprises whilst simultaneously leading to some of the most notorious data breaches in history, such as Cambridge Analytica. As Musk teeters on the brink of launching possibly one of the most successful biotech products in history, personal privacy is at peril. Though legislation exists to regulate the transfer of personal data, such as the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), it is unclear whether data sourced from the Neuralink device falls within the purview of such laws.

The EU has also recently authorised new powers to be used against technology monopolies. The mandate permits the exclusion of large tech groups from the single market altogether if they fail to comply with the methods prescribed to ensure that information on users is gathered consensually. Neuralink’s ability to amass cosmic amounts of intimate data, combined with the creeping distrust towards thriving tech companies, may cause internal struggles and perhaps consolidate festering fears amongst consumers.

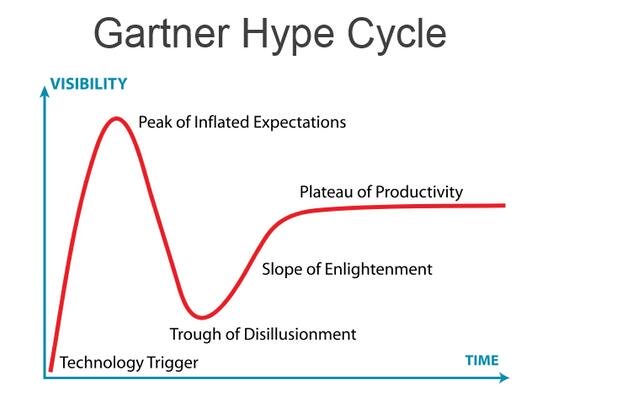

Yet consumers may not initially be all that perturbed when it comes to the exploitation of data. The technology’s nightmarish sci-fi potentiality poses more of a threat to its commercial success. By way of human nature, consumers will always doubt whether new technologies like Neuralink are viable and effective. Similar mistrustful attitudes surged following the launch of commercial space travel and active technologies, such as Blockchain, that have since passed the ‘peak of inflated expectations’ on the Hype Cycle. Neuralink’s novelty is the root of all misgivings surrounding its functionality. Despite Musk’s ‘three little pigs demo’ the likelihood of the technology working on humans is still disputed.

Novelty

However, this so-called novelty can also be challenged. Neuralink devices are not too different from micro-chip technology recently launched in Sweden. The Swedish chip is typically inserted into the skin just above the thumb using a syringe. It centralises personal information, including emergency contact details, social media profiles, identity cards and documentation, health records, bank details and much more. All the information can be accessed by swiping the chipped thumb against a digital reader. Though the benefits of Sweden’s micro-chip technology cannot rival the potential medical breakthroughs Neuralink’s brain interface proffers, conceptually both devices are very alike. The success of Sweden’s thumb micro-chips could foreshow widespread acceptance for Neuralink’s considerably more invasive product.

Proponents of Musk’s Neuralink will inevitably argue that the technology’s ability to provide treatment for untreatable medical conditions far outweighs the risk it poses. Even if the technology does deliver in terms of functionality and safety, the potential siphoning of personal data remains a conceivable danger. The value of data in today’s day and age is grossly underestimated; it forms the substructure of our economy and both subconsciously and consciously informs our spending habits as consumers, influences our thought process, and shapes our choices via targeted advertising. The consequences associated with allowing access to neural patterns that so precisely predict how we respond to the content we consume, the food we eat, and the people we interact with, may not seem significant. But it is.

Providing an opportunity for corporates to utilise our data by supporting ideas like the Neuralink brain-chip will alter our material reality – not in the fantastical futuristic way that many of us currently perceive, but in a much more subtle yet equally profound manner. The question left to answer is if the medical silver-lining is worth sacrificing control over personal information. Should we allow conglomerates to construct our expectations by misusing our personal information and enable them to tailor our reactions to the world for commercial gain?