Ravaged by the economic ramifications of the pandemic, the energy sector has regressed into one of the worst declines ever witnessed in the last century. As the demand for oil plummets, the sought-after black lucre that once formed the groundwork for widespread geopolitical instability is gradually losing its political leverage. Nascent renewable alternatives are being integrated into the energy mix – corroborating the declining social importance of oil. The non-commercial implications of this could give rise to a new political milieu in which energy democracy is a central player.

Why is oil on the decline?

As a catalyst for aggressive foreign policy, oil has historically formed the basis upon which many political decisions have been made. It has become a global linchpin and dictates the responses of major players in the economy. So, if this is the case, why has there been a downturn in the market and how has Covid-19 exacerbated this?

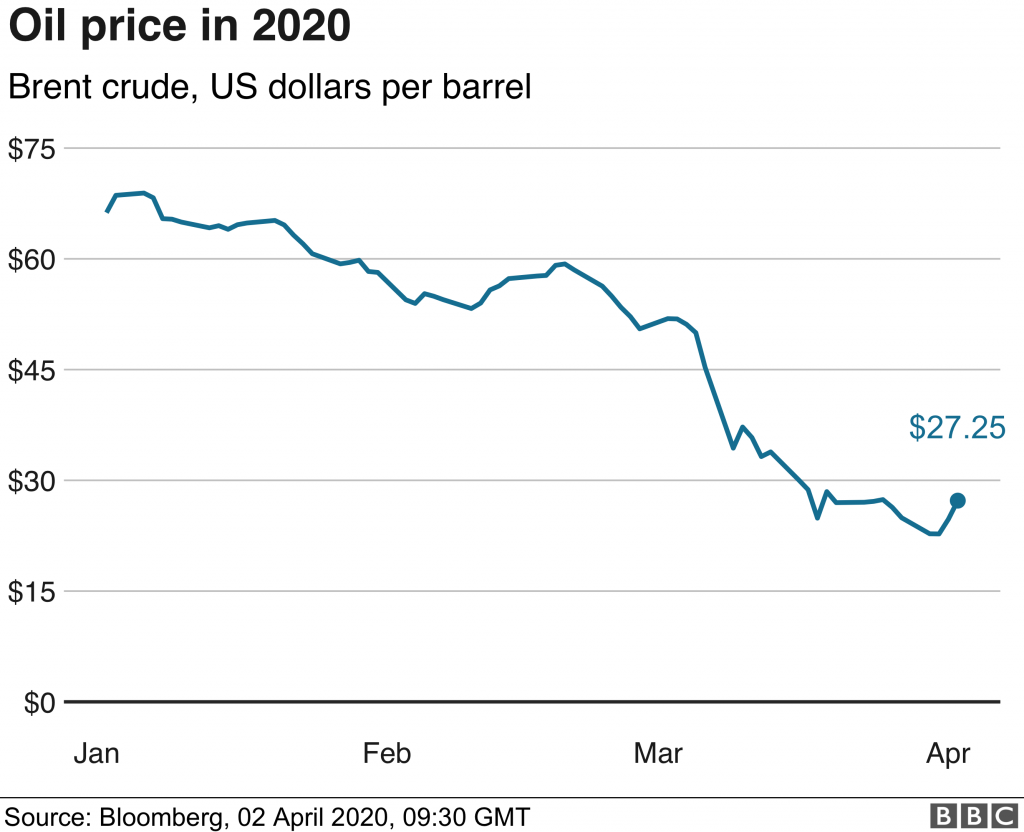

- A decrease in demand: the most obvious reason why the oil industry is predicted to crash and burn is the lack of demand in the wider economy. Remote working has become increasingly popular resulting in reduced transport and production costs for individuals and businesses – eroding oil value as demand continues to drop.

- Price-wars: geopolitical volatility is inherent in the trade of commodities such as oil, mainly due to the fact that some regions are richer in the resource than others. Price wars have emerged as a consequence of this disproportionality and have deepened this innate tension. The most recent price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia has enhanced the demand side shock of the pandemic.

- The Paris Agreement: this has rendered 51% of assets as completely worthless; only 41% of carbon can be burnt in order to stay within the 2-degree mark of change. The outward value of many oil companies has therefore diminished on the balance sheet and has reduced investor enthusiasm.

What is energy democracy?

As this downturn continues, renewable alternatives are coming to the fore. The idea that regions which choose to adopt a green transition will have to undergo social, institutional, and cultural innovations and regulate destabilising power relations is what we call energy democracy.

How will it work?

Implementing a technical and social transition involves overhauling monopolised fossil fuel energy systems – in other words, dismantling cartels such as OPEC or groups such as the Gas Exporting Countries Forum.

This has the power to change global power dynamics once and for all. By retaining majority control over a hot commodity (such as oil), cartels have the capacity to shape global relations and provide cardinal anchorage for countries embroiled in political warfare.

But how feasible is energy democracy exactly? Although a stream of renewable energy substitutes has been established, oil is still prevalent in other downstream services such as the production of petrochemicals, natural gas, clothing, and other products.

If there is still a vested interest in products of this nature, the oil industry as a whole cannot be written off entirely. If this is the case, how feasible is it to preserve organisations such as OPEC? If they are retained, will its political influence be tempered by the pandemic?

Understanding how pragmatic this parallel universe of energy democracy is depends upon the trajectory of the oil industry as a whole and the demand for petrochemicals in a post-pandemic future.