by Hajra Tahir

Amid the recent cries for war, cross-border division, imminent violence and conflict – the origins of the Kashmir crisis remain unclear.

A contentious region situated in the lower area of the Himalayas – Jammu and Kashmir’s geographical proximity to both Pakistan and India are amongst one of the many reasons for its long-term territorial ambiguity. Kashmir has for over four decades resisted interference from neighbouring nations and maintained a shaky sense of self-determination. As of the 6thof August 2019, however, the contravention of this autonomy by the Indian government resulted in world-wide uproar. Before delving further into the crux of the conflict, it is essential to grasp the colonial origins of the dispute in order to understand how Jammu and Kashmir became the controversial location it is today.

Colonial History

The Indian subcontinent was amongst the many areas annexed and exploited by the English during the early 1600s. Inspired by the lucrative ventures of Portuguese merchants who successfully established trading businesses in the region, the British East India Company was created by English merchants aiming to emulate this success. The firm was given a monopoly of all English trade in Asia through a royal charter issued by Queen Elizabeth I. Towards the end of 17th century however, India became the hub of the company’s business endeavours. After securing a patch of land in the southern region of Madras (now known as Chennai), the company increased the breadth of products up for trade as well as expanding the business throughout the country – consolidating their ownership of the region.

Demise of the Mughal Empire

This lengthy annexation came to an end as the Mughal empire, began to deteriorate. The empire provided the framework for British business endeavours and its eventual demise was due to the increasing prevalence of the Maratha Empire in the central west of India.

The contending empire consisted of a sub-sect of Hindu warriors, originating from the Western Deccan Peninsula. The dominance of this new kingdom meant that an alternate milieu began to gain traction in the subcontinent – Hindu revivalism became entrenched in Indian culture and expunged Sufism and the architectural legacy of the Mughals. It can be argued that nationalist sentiment in India became prevalent from this point onwards in history. The empire was symbolic of the waning power of the Muslim rulers, and in conjunction with the faltering influence of the East India Company, its mere presence inflamed patriotism and an ethnocentric undercurrent which persists in India today.

The Sikh empire also resisted doing business with the firm, further contributing to an increase in Indian national self-consciousness. These sentiments spiralled and eventually manifested themselves in the Great Indian Rebellion of 1850 which eventually lead to the complete destruction of the Mughal empire and the transfer of sovereignty, from the East India Company to the British Crown directly.

The Raj

Extensive exploitation of Indian resources to fuel the industrial revolution; countless deadly famines; the failure of the Maratha empire to fill the political vacuum left by the Mughals and the use of British ‘divide and rule’ tactics to aid imperialist expansion, resulted in political anarchy in the subcontinent. The dire situation of the nation escalated as more resources were being siphoned to help the war effort. However, the various European defeats suffered by the British between 1940 and 1942 destroyed the foundations of the Imperial system and further exacerbated disarray in the continent.

Post-Colonial History

The full extent of Indian colonial history is difficult to condense into four succinct paragraphs, however, the implications of a two-century reign of brutality are even more intricate and difficult to unpick. One overarching social consequence of Britain’s legacy in India is the creation of religious discord within the country – a factor that is integral in causing the Kashmiri rift.

While the British were fighting in World War II, they struggled to simultaneously fund their occupation of India. 40% of India’s wealth was spent on maintaining the British army yet despite this, the British were getting incommensurate returns on this significant investment and suffered cardinal losses in battles such as Dunkirk and Singapore in 1942. It was becoming increasingly difficult for them to keep their standard 20,000 troops deployed in India, resulting in the need to alleviate this burden through increasing internal conflict within the population. This led to the resurgence of ‘divide and rule’ tactics.

The gradual introduction of modern education systems, reserved jobs for certain castes in government institutions and the start of census operations, became the substructure upon which divide and rule tactics took flight. The aim of these policies introduced by the British was to fortify class differentials and westernise certain sects of society to make them sympathetic to the British cause. Over the years these differences in class, religion, social standing and education became ensconced within Indian society along with an increasing nationalist sentiment. Conflict between Muslims and Hindus were particularly violent and resulted in two main political parties forming to protect the interests of the respective groups: The All-India Muslim League headed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Indian National Congress headed by Jawaharlal Nehru. The surge in violence between the two groups in landmark massacres such as the Great Calcutta Killing, a four day blood-bath in which over 10,000 civilian lives were lost, became the catalyst for partition and the starting point in the Kashmiri crisis.

Formation of Kashmir

After internal dissension threatened to overwhelm the weakening influence of the British, a consensus was reached that partition was necessary. The man responsible for the hasty reorganisation of the entire Indian sub-continent was the British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe who established the ‘Radcliffe line’ that eventually served as the formal geographical cut off point between Pakistan and India.

Radcliffe had not been to India, nor anywhere else in Asia, yet was tasked with completing a 5-year expansion within 4 months. His lack of knowledge regarding Indian straits and geography supposedly made him an impartial figure who could devise the composition of each country without any interventional bias. However, this alleged neutrality was defunct and did not contribute towards improving the demarcation since the last Governor General, Lord Mountbatten and his wife Edwina shared a close relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru. By influencing the commission on behalf of his friend, Lord Mountbatten’s insufferable interference from the very onset disturbed the allocation of the princely states – including Kashmir. Due to its peripheral position in the subcontinent as well as Mountbatten’s preoccupation with administering the prosperous regions in line with his own social interests – the state was left alone with a 77% Muslim majority population ruled by a Hindu king. This led to a constant tug of war, causing somewhere between 20,000-100,000 Kashmiri deaths in the Jammu massacre of 1947, a mass migration of many Muslim Kashmiri’s into Pakistan and the first Indo-Pak war in 1948 – the agenda of which is still pertinent today.

Rise of Nationalism in India

An increasing sense of urgency to resolve the Kashmiri crisis has set in due to the surge of populism in India caused by a new age of government, inflammatory incidents of violence and the creation of controversial cinema. The deteriorating sense of tolerance in the world’s largest democracy directly impacts the Muslim minority and has further exacerbated the religious divisions in the highly disputed region of Kashmir.

Although the cultivation of nationalistic values is predominantly a product of colonial rule – as highlighted several times throughout this article – Narendra Modi’s government has amplified the frequency of religion-based violence.

Statistics show that in the three years leading up to 2017 there has been a 28% increase in communal violence, pogroms and targeted attacks on Muslim businesses – particularly those involving cattle farming. The aggression has escalated in states with a majority supporting BJP (Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party) since Modi’s term started in 2013. This growing animosity towards Muslim minorities in particular has led to India being ranked fourth after Syria, Nigeria and Iraq as having the highest social hostilities involving religion – the figure for religiously aggravated crime peaking sharply since 2014. The growing racial tensions became highly publicised in 2015 when high profile Bollywood stars were being threatened by fundamentalists as a result of acting in the period drama ‘Bajirao Mastani’ – a Bollywood rendition of the events that unfolded between Peshwa Bajirao, the Hindu general of the Maratha Empire and his Muslim lover Mastani.

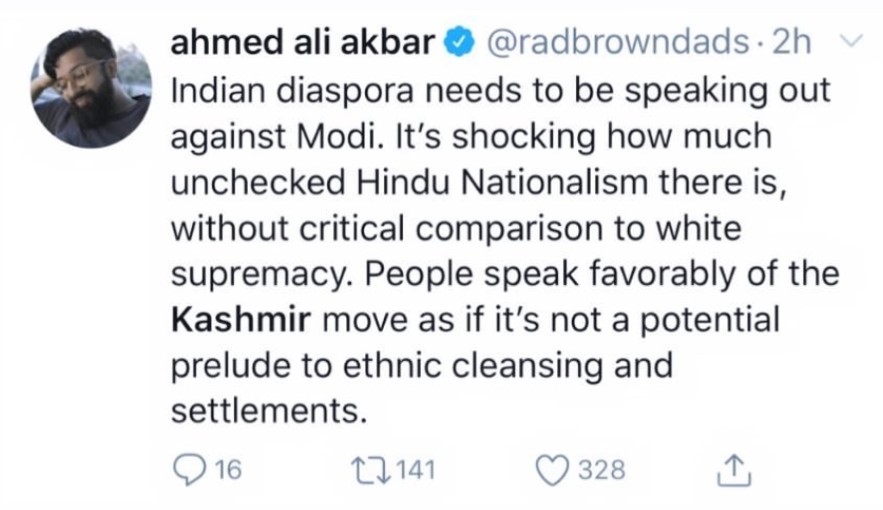

The frequency of unconscionable racial attacks seems to have negated the validity of Kashmir’s religious claim to autonomy on the basis of being India’s only Muslim majority ‘state’ and has strengthened a national desire for complete insurgency of the region. Some argue however, that the prevalence of reactionary fundamentalist activity heralds a darker future for the limbo ‘state’ that involves reshaping the demographic of its population through ethnic cleansing.

Present Situation – What Actually Happened?

Now that the we’ve thoroughly explored the historical, geographical and political context of the conflict, it’s time to focus on the legal changes that have renewed the global turmoil.

The key piece of legislation in question is article 370 of the Indian constitution. When Kashmir was intruded in 1947 post demarcation, by Pakistani tribesmen, the Hindu King (Hari Singh) appealed to Governor General Lord Mountbatten to provide military aid to quell the uprising. The letter through which he drafted his appeal also contained an instrument of accession to India that he himself signed. The document therefore allowed defence, external affairs and communications to be controlled by India whilst matters related to all the other sectors would be retained by the ruler under the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution Act 1939.

This resulted in a peculiar middle-ground state of autonomy for Jammu and Kashmir that differed from the complete accession of the other 565 native states. However this strange period of semi-control, (punctuated by frequent efforts to subdue civilians who protested the presence of Indian military in the region), recently came to an end as the Jammu and Kashmir Redistribution Bill was introduced in the upper house of Indian Parliament. This Bill was implemented to reverse Kashmir’s autonomy. This is problematic because of the following.

The BJP had been campaigning for a unified India before being elected with the following stipulations regarding reform as the forefront of their campaign:

“…be done in a manner which assures liberty to all Indians through a range of other reforms detailed elsewhere, and allows good governance to be established everywhere in India. Only after the rule of law along with equal opportunity has been brought to all Indians, will we request a recall of the J&K Constituent Assembly (as required by Article 370(3) of the Constitution) to consider this amendment. Without the goodwill and consent of the people of J&K, such an amendment will violate the spirit of democracy and liberty”.

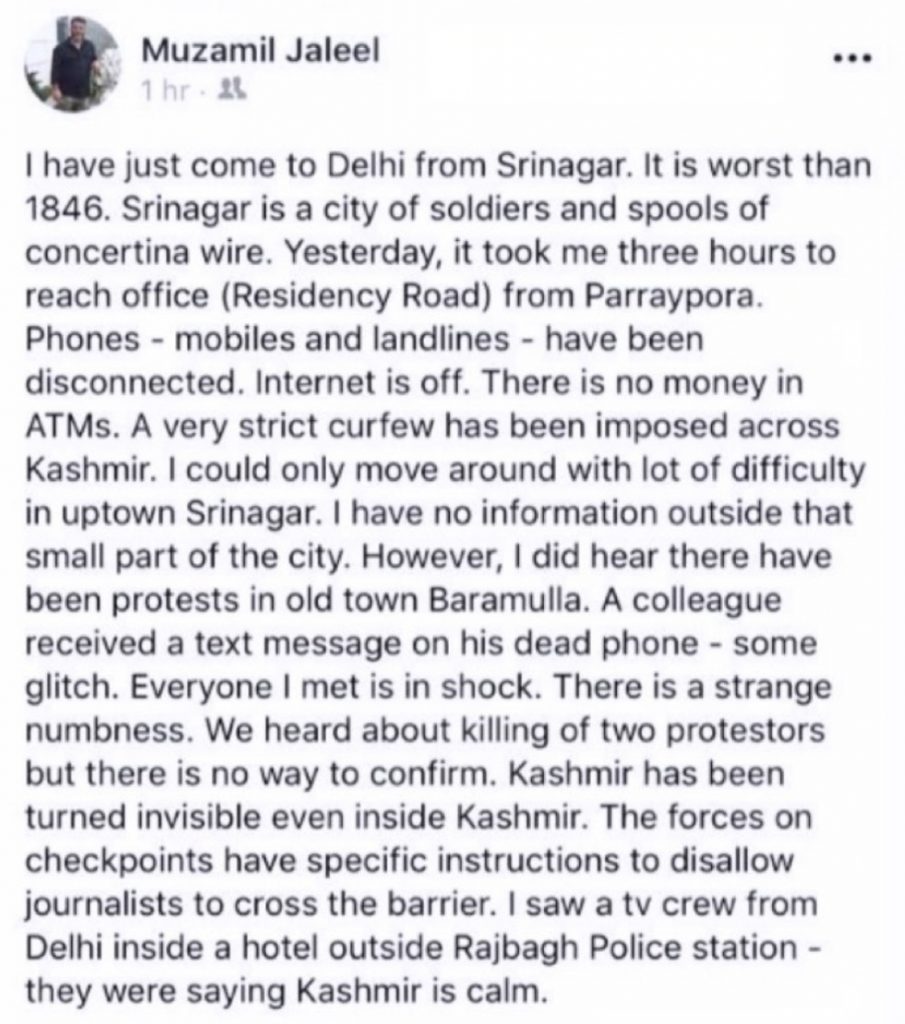

This was clearly not implemented nor considered by Modi and Indian parliament when re-constructing the redacted bill. As Kashmiri’s retaliated to being unfairly stripped of their freedoms by taking to the streets of Sringar in the largest demonstration since the lockdown of Indian administrated Kashmir, the government continued to suppress protestors using pellet guns and tear gas. The Government later denied any such suppression happened.

Not only is this a clear subversion of democracy, there is an impending danger that the more players will intervene and further lives will be lost as China has publicly pledged to support Pakistan in their decision to approach the UN Security council in the wake of India’s decision to revoke article 370.

It is unlikely that the crisis of Kashmir will be resolved anytime soon. It draws many historical and political parallels with crises such as the Palestine-Israel debate and similarly shows no sign of being resolved. Many feel that the best solution available is to hold a referendum – yet the likelihood of such an outcome is rare due to the neighbouring nations of China, India and Pakistan’s vested interest in the hotly debated piece of land.

Hajra Tahir is in the first year of her undergraduate Law with Politics degree at the University of Manchester. With an interest in international relations, literature and travelling she aims to hopefully supplement her future career as a city lawyer with pro-bono work and an involvement in civil and human rights.