‘Yeah, I’d say I’m pretty left.’ They said, nervously circulating their gaze around the group, hoping the topic of discussion would move on.

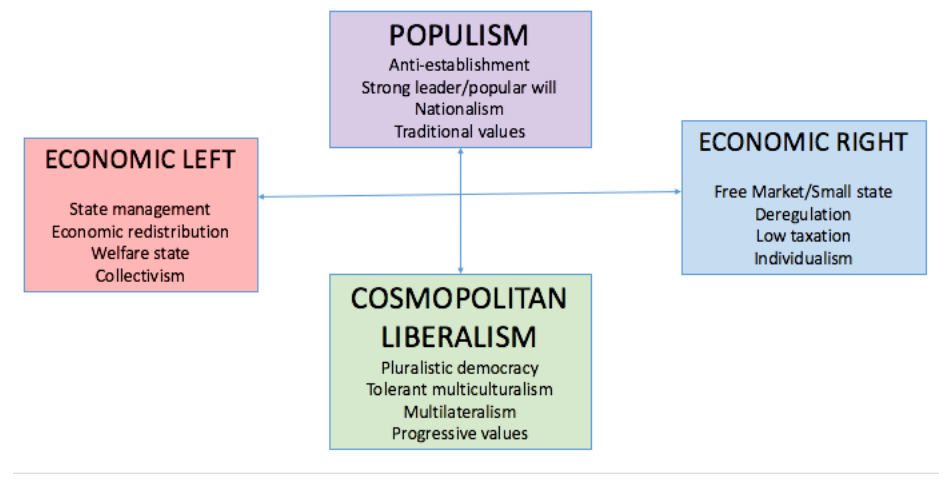

But what does being left-wing actually mean in 2018? After decades of people being split separate ways by a growing plethora of issues, can a simple left-right border line describe much about us at all? We are right to feel confused by a measure like this.

Where does left-right come from?

Originally it comes from a debate in 18th century France. The left, who were against the idea of a monarchy, opposed the right, who supported it.

In the UK, the left-right wing split was most prominently defined by a debate over how the government should manage the economy, after World War 2. The Labour party on the left, believed that industries such as the bank of England, coal, and transport, should be managed under government ownership, funded by taxation. The Conservatives, on the right, thought the government should let industry be privately managed by businesses, resulting in lower taxes.

However today this discussion is far less contested. In the decades following, a broad consensus was reached that the majority of these industries should became privately owned. By this measure Britain’s overall stance as a country is ‘right wing’. That’s right, you’re right wing.

In the absence of calls for nationalisation, the right-left divide became largely about debates over social welfare, education spending, minimum wage and benefits.

In addition, social concerns surfaced as a large cause of divide amongst voters; attitudes towards issues such as women’s rights, LGBT rights, religion, and race, gained ‘left-right’ status.

This made being left or right wing a delicately built hybrid machine, made up of a growing package of views. Either side carries connotations of beliefs on the government economic role, the monarchy, immigration, attitudes to love life and everything in between.

This is problematic. There are lots of people who care about the environment but favour a monarchy or low taxation. Equally wanting higher taxes or opposing a monarchy doesn’t guarantee your passion for the environment, show that you want to remain in the EU, reveal your thoughts on immigration, or guarantees your opinion on LGBT+ for that matter

A Global World

Unfortunately, things aren’t getting any less complicated. Every day that we roll out of bed there will be new issues we have to force into the overcrowded left-right compartments.

A lot of our debates today are in fact no longer nationally confined but centred around global issues, such as climate change, national identity, the morals of artificial intelligence, and the EU.

Let’s take Brexit. The biggest debate of our time has been sided by an unconventional formation of left-right thinkers. With the desire to leave the EU having been championed by right wing voices like Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson, but also previously long campaigned for by ‘left-wing’ Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

On the flip side, the voice of remain is made up of a mixture of left-right voices from Labour’s Chuka Ummanu, to Tony Blair, to Conservatives David Cameron, and George Osborne.

With all this clutter in mind, trying to make yourself into a person that can align as left or right wing causes more than a headache. It isn’t really possible for most of us. In reality these right-left camps are becoming more associated with identity or moral connotations rather than having any particular meaning.

For example, universities are left wing places, where it is good to be left wing. But in practise we all at university have our individual takes on these complex bundles of issues, which would fail to complete the paradigm of being ‘left wing’. In this respect being left or right wing might better describe where we are, rather than who we are.

We need to update ourselves to new times. To avoid being trapped into the left-right debate. If anything, these false homes prevent our ability to discuss issues in detail, by checking our broken political compass for guidance.