Michelle Rapoport is a Policy Fellow of The Pinsker Centre, a campus-based think tank that facilitates discussion on global affairs and free speech. The views in this article are the author’s own

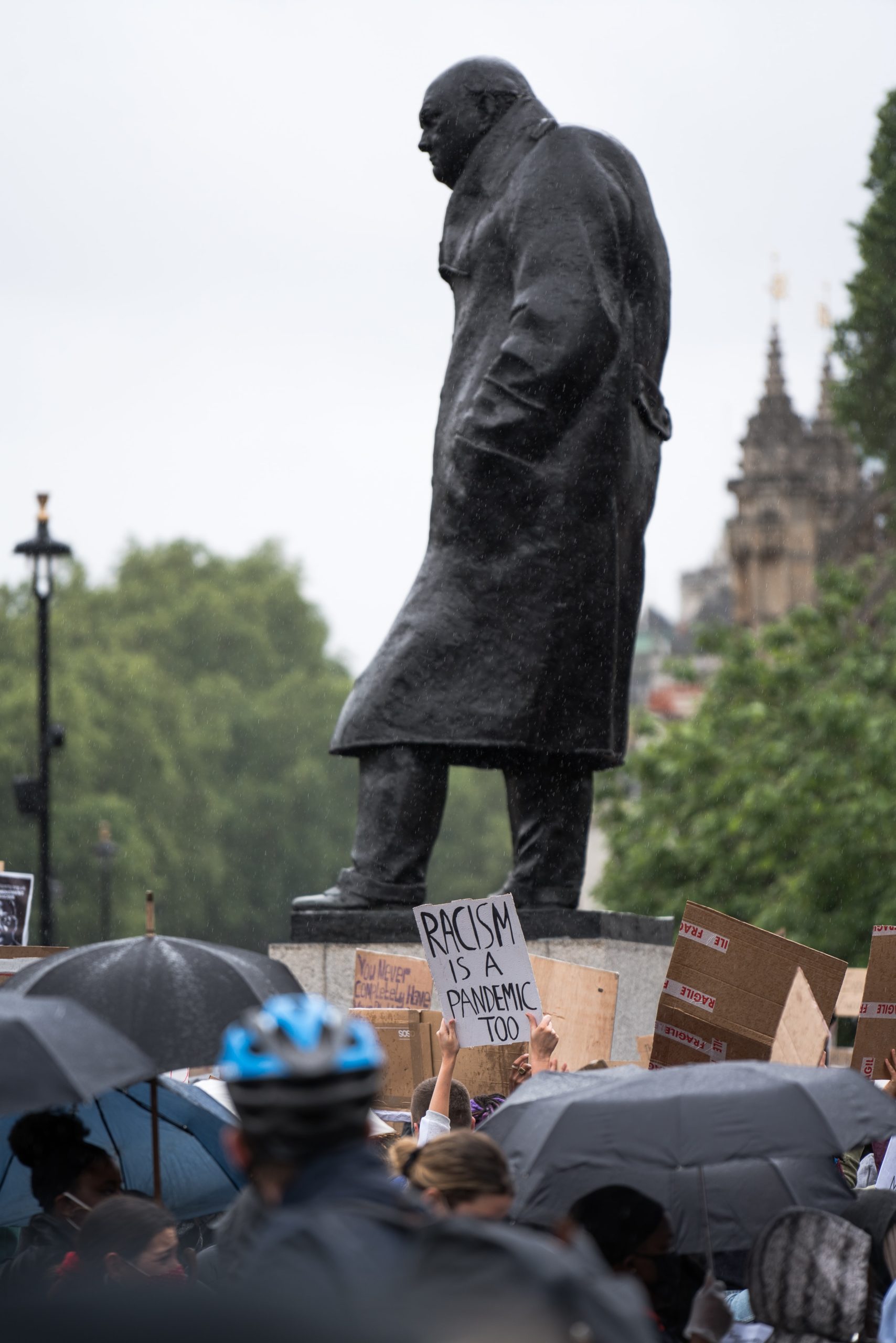

The summer of 2020 was an explosion of political demonstrations, from anti-lockdown riots, pro-Palestine marches, to the George Floyd rallies. In the wake of pandemic protesting emerged a sub-stream of grassroot activism inciting the removal of Confederate and colonialist statues.

On June 2020, some 1,000 demonstrators gathered in Oxford’s high street to peacefully protest the statue of Cecil Rhodes outside Oriel College. The effort was ignited after slave trader Edward Colston’s statue was torn down by protestors in Bristol, and an online petition with 150,000 signatures calling for Rhodes’ removal rapidly gained traction.

A year later, the college’s governing body decided that they would not be taking down the statue due to ‘regulatory and financial changes,’ a verdict that was applauded by the then-Secretary of State for Education, Gavin Williamson, who tweeted:

‘We should learn from our past, rather than censoring history, and continue focusing on reducing inequality.’

The attitude of the Education Secretary can be reflected in our own history textbooks. The national curriculum for history is committed to educating pupils on infamous conflicts and their perpetrators, with the primary aim of preserving the historical narratives for future generations.

Yet, the textbook education that most of us receive from primary school, differs substantially from the one-dimensional glorification conveyed by grand memorials. Scattered around cities in Britain are imposing statues portraying bygone figures, immortalising Britain’s history, literally, into stone.

While ‘eye candy’ for the enthusiastic tourist, these statues also represent a moral quandary. Which historical figures should we memorialise, and what are the implications of doing so?

The Rhodes Must Fall movement is a symptom of this quandary. The movement answers it by arguing that certain historical personalities epitomise racial supremacy, misogyny, and other values of European colonialism that have no place in the twenty-first century. A Rhodes scholar himself, Joshua Nott, likened a statue of Rhodes in Cape Town to ‘a swastika in Jerusalem.’ Ergo, the primary goal of removal campaigns is to obliterate these offensive ideals.

However, in modern times, it can reasonably be argued that most people in one society follow a similar moral compass, regardless of where they fall on the political spectrum. Hence, varying views about statue removal rarely pertain to the ‘ethical score’ of a bygone colonialist, but rather the medium of preservation in our society by way of elaborate monuments.

As summarised by Vice President for Graduates at Oriel College, Neil Misra, the administrative response to the 2020 protests was:

‘a signal of Oriel College’s willingness to adapt to the times and listen to the demands of the students…to help make the college and university more welcoming for [BME] students.’

Misra’s comment has aged poorly – a report published by Oxford University indicated a majority of BME students feeling indifferent about the removal of the Rhodes statue, citing that it would not affect their personal experience at the university, thereby undermining a core tenet of the Rhodes Must Fall movement.

More significantly, indifference to a statue’s presence is reflected across other campaigns prompting its removal, suggesting that there may be more fruitful ways to improve campus life than the removal of a statue.

Yet, protesters continue to argue that to consign colonial views to the past and to prevent damage being done to the personal and academic experiences of BME university students, it is imperative to wholly remove such figures from public view.

Crucially, statues of colonial figures symbolise more that just that individual’s own views. They represent Britain’s past mistakes, which paved the road for Britain’s contemporary society. Cambridge scholar Mary Beard developed this rationale by proposing a solution to ‘[not] pretend that those people didn’t exist’ but rather to ‘empower [students] to look up at Rhodes with a cheery and self-confident sense of unbatterability.’

To achieve this sense of empowerment, the physical markers of British errors should become educational tools, akin to the introductory texts of primary school history. In order to achieve this, former UK Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden argued that we should simply ‘explain’ monuments because ‘[we] must defend our culture and history from the noisy minority of activists constantly trying to do Britain down.’

In January 2021, the Government affirmed this approach in the announcement of new laws to ‘retain and explain’ historic monuments. Contextualising offensive ideals -through education – would far more effectively eradicate the effects of glorification that removal campaigners – albeit rightly object to. In turn, this would promote the honourable virtue of safeguarding history.

In short, the biggest danger posed by problematic statues – veneration of dangerous ideals – lies in their extravagant medium. But can we reconcile our efforts to ‘explain’ monuments with the blatant splendour of marble and stone? To remove statues is essentially to censor and whitewash history. Although we cannot erase the past, we can certainly judge it, and pass our lessons on to the next generation.

Ultimately, if we burn the books, we have no context with which to measure achievements and reflect upon mistakes. We must endeavour to harness the power of marble and stone for education and to inculcate the lessons of our nation’s past.

Michelle Rapoport is a Policy Fellow of The Pinsker Centre, a campus-based think tank that facilitates discussion on global affairs and free speech. The views in this article are the author’s own