The Olympics foster sportsmanship across the world and provides a platform for elite athletes to gain global recognition. However, more than just an international competition, the Olympics is a huge business. The broadcasting television network NBC recently paid $7.7 billion for broadcasting rights to show the Olympics up until 2032. The games also generated over $1.5 billion in ad revenue prior to the broadcasting. Similarly, the sheer popularity of the Olympics also means that host countries are likely to experience a surge in GDP as incoming spectators spend their money on local businesses. Yet despite this year’s lack of live viewers, an NBC executive has dubbed Tokyo 2020 as the most profitable Olympic games yet.

Olympic Costs

It is clear that the Olympics is a lucrative spectacle but the prestige associated with competing in the games often overshadows the fact that athletes are not given a cut of this profit. It is a well-known fact that athletes like Simone Biles, Michael Phelps and Usain Bolt have used their Olympic fame to launchpad their own businesses and multi-million dollar endorsements – resulting in massive networths and notoriety. However, the same cannot be said for the 11,000+ others who have made similar sacrifices to pursue their Olympic dreams.

Recent examples include Riley Day, an Australian Olympic runner who worked at Woolworths for three years to fund her Olympic campaign. Day came to the Olympics with no corporate sponsor funding her travel and training expenses. Much like Day, US Olympic figure skater Adam Rippon admitted in 2018 that he used to ‘steal apples from his gym’ because he was so broke in the lead up to his Olympic win. It is clear from these examples that lesser-known athletes struggle financially. A study of 500 elite athletes found that 60% would not consider themselves to be financially stable. This figure is better understood when the costs of being an elite athlete are taken into account. 5x US Olympic runner and bobsledder, Lauryn Williams, estimates the total cost of conditioning therapies, coaching expenses, nutritionist salaries and equipment to be upwards of $124,000 – way more than the average athlete can afford.

How do Athletes Make Money?

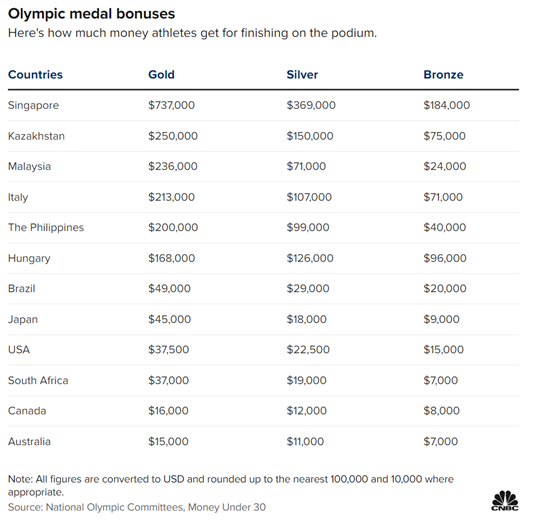

Olympic wins undoubtedly bring much coveted ‘glory’ to the countries whose elite athletes outperform their competitors, but the idea of bolstering national pride has not motivated many governments to fund the Olympic careers of their budding talent pool. The US government does not directly get involved in funding the Olympic team and the US Olympic and Para-Olympic Committee instead provide a stipend to support American athletes. However, as stated by US Olympic rower Megan Musnicki, her total stipend amounts to a meagre $2000 a month and for athletes competing in less mainstream sports such as fencing it can often drop to as low as $300 a month. Another source of funding is prize money. The following shows the amount each country awards its Olympic gold, silver and bronze medalists.

Many countries such as Singapore award huge cash bonuses to their gold medalists and remunerate them for participating in the games. Kazakhstan, Malaysia and The Philippines also dish out hefty bonuses however the same cannot be said for countries such as Japan and the US which currently holds the most gold medals.

Sponsorship Problems

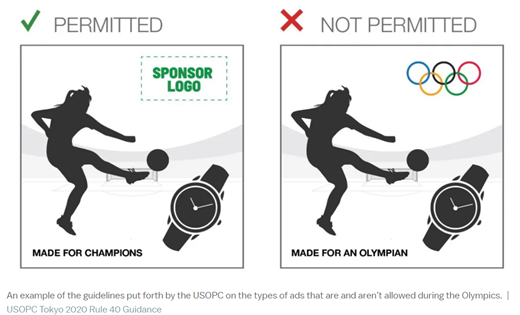

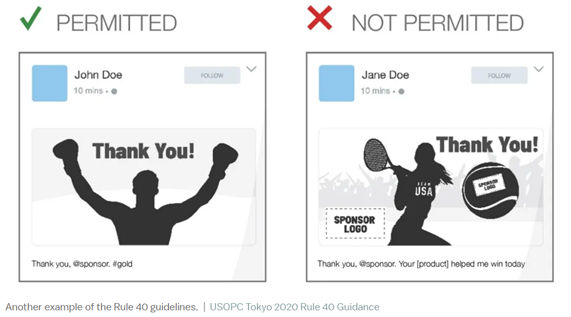

Prior to the 1970s, Olympic athletes were considered to be amateurs competing solely for the ‘love of the sport’. Since then, rules have been relaxed to compensate athletes in correspondence with their training efforts. Yet many aspiring Olympians are still hamstrung by Olympic sponsorship rules that restrict them from utilising the huge advertising platform they are given every four years. The IOC has used ‘Rule 40′ to control how much exposure individual sponsors get in the Olympics – the rule states that only official Olympic sponsors are able to take full advantage of the platform. The use of athletes’ names, performances and personal images is severely limited under Rule 40 and they are often prevented from using Olympic language and symbols when addressing their individual sponsors. US athletes can only post 7 thank you messages referring to their individual sponsors and are limited to receiving one post of congratulations per sponsor.

The debate over whether Olympic athletes should be paid is not new. The same sentiment has been rife in countries like the US where college athletes have also been campaigning for a base salary and the ability to cash in on sponsors and viral performances. This is explained in the following video of college gymnast, Katelyn Ohashi.

Should Olympic Athletes be paid?

Rules that prevent athletes from touting their personal endorsements on the Olympic stage are seen by the IOC as reasonable because they stop the official Olympic sponsors from being subject to ‘ambush marketing’ but such regulations undoubtedly hinder athletes financially. Many Olympians (and other athletes) have sidelined their careers to achieve their goals as training and conditioning is a full-time commitment that takes time, money and energy. Bearing in mind the massive physical, financial and personal sacrifices these sportsmen and sportswomen make, proper remuneration and an ability to capitalise more freely off their personal brands is arguably their right. Over the years, following campaigns like #WeDemandChange (started in the London 2012 Olympics), sponsorship regulations have been gradually relaxed and the IOC are allegedly working towards creating a more balanced system of remuneration that benefits athletes and maintains Olympic profit margins.