In a time where crime in our capital is at an all-time high, the narrative we often see in the mainstream media is that people of colour, are using violence to channel their pain.

This is only part of the story. There is a growing group of BAME men and women, using their experiences to inform their art.

In our 10 part feature, we meet some of these artists. These artists are swimming against the tide, creating a lane for themselves. They talk to us about the Cost of Artistry.

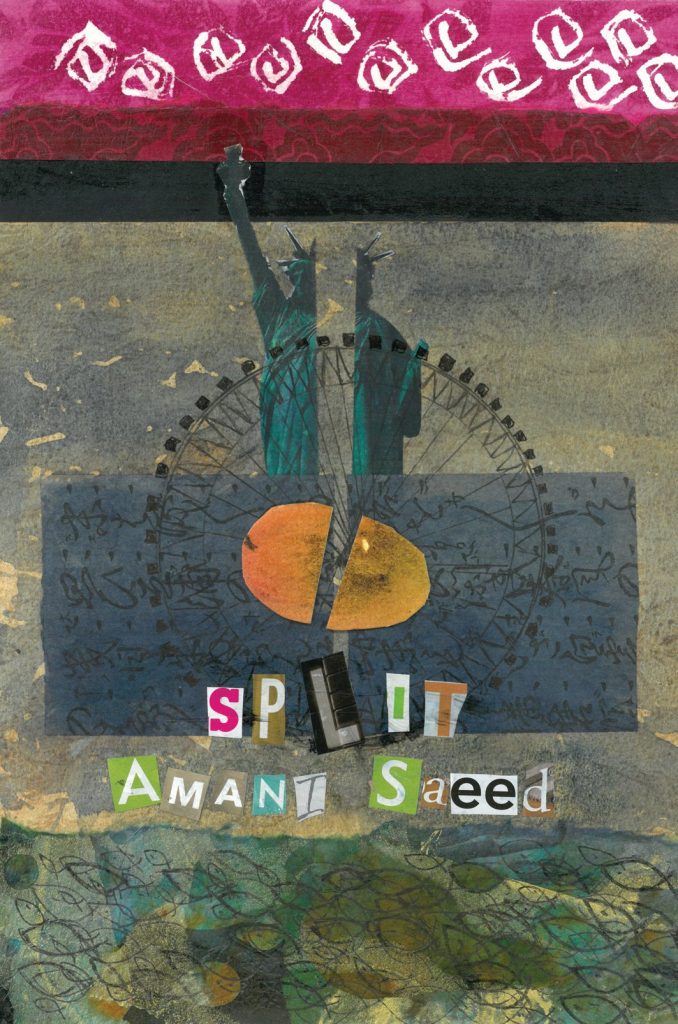

8/10 meet Amani Saeed

When did you discover you had a “talent”?

When my mum told me so – kidding (kind of)! The first time I realised people liked my work was when I started performing at my local open mic. I was 19 and studying at Exeter, which is a predominantly white institution. It was the year Daesh had come to the forefront of the news with their beheading videos, and I was writing about what it meant to be a Muslim woman living in the wake of that cruelty. The poetry I wrote and performed resonated with the audience to the extent that I started getting booked for shows, doing radio interviews…it was exciting to me that people cared about the ideas I was expressing.

What have you had to sacrifice to nurture your talent?

Sleep. When you’re working a 9-5 job, if you want to grow as an artist, you have to be deliberate about dedicating time to your craft. That means writing poems on the tube in the morning, doing admin during your lunch break, and using up your annual leave to go on Arvon retreats and do gigs. It means stumbling home at midnight from an open mic knowing you have to be up again in a few hours. None of this is glamorous, or even healthy, but at the moment, it’s what is necessary to keep me growing as an artist.

I’ve also had to sacrifice my pride in order to grow. A friend gave me a great piece of advice – “if it scares you, you haveto do it.” This means taking calculated risks: performing pieces outside of my comfort zone, at events outside of my comfort zone. And sometimes that means bombing on stage. But you can’t grow from what you don’t learn from—so I fail gladly knowing that every failure is an opportunity to rise.

Who inspires your artistry?

The inspiration for my artistry comes from listening to rap, from artists like Kendrick, Missy, J. Cole, JID, Eve. From their music, I’ve learned the importance of flow, of rhythm, of pacing. Poetry is lyrical, whether it’s on the page or on the stage, so I always want my work to be technically sound. There’s a theatricality to rap that’s also made its way into my performance style. Rap teaches you confidence: to be bold and to trust your tongue. It also teaches you how to throw your voice—how to slow it down, speed it up, harden it, soften it— so that it holds people’s attention. I find that the way you play your voice can take your audience on a journey as much as the narrative of your poem can.

What is the biggest misconception people have about poets?

That we’re social justice warriors shouting into idealisms into an echo chamber. Poets are so aware and attuned to the environment they’re in. We’re constantly reacting, whether it’s in response to a news segment from across the Atlantic, or to something happening down the street.

In an age where digital echo chambers are growing wider, what role do you think poetry can play in this?

Poetry, especially when it’s performed, has the special power of being able to reach into a chest and touch a heart. It takes big, intellectual, sometimes alien concepts such as racism, sexism, and homophobia, and packages them into something a listener not only can understand, but can careabout. I would even go so far as to say poetry has the ability to bridge the divide between different communities. There is nothing as humbling or as empowering as listening to someone’s story.

Has a poem ever humbled or frightened you? What was it? When did it happen and what did you do afterwards?

Liam McCormick’s show ‘Beast’ scared the hell out of me. It was midnight and he was performing at the end of the Fringe to an audience of 4 people. He’d seen me performing a piece about sexual assault earlier in the evening, and when he was performing his poem about male violence, he didn’t break eye contact with me once. I’ve never felt so outraged or confronted by a poem before. It was frightening and humbling because after a really shouty section, his voice lowered and his eyes dimmed and he said “I am sorry”. It was the apology I never received from my abuser, and I’m grateful for it.

Some poets claim that a poem is like a living creature: once it’s out there is not much you can do to ‘correct’ or ‘improve’ it, while others edit meticulously, not leaving much from the original, draft form. What is your take on it?

To an extent, it depends on the form you’re using. When it comes to spoken word, I change my performance each time; you can’t perform a poem the same way twice because you’re not the same person at each performance. But when it comes to print, it’s like floating Moses out in a basket. That baby is out there and you can’t get it back. And to be honest, whether your poem is out on the page or on the stage, your intention is no longer relevant. You, the writer, had the opportunity to craft what you wanted to say. What becomes important is how the poem is heard and perceived and how it resonates with its audience – it is almost arrogant to impose your own intent on a poem after you publish it, because it is no longer yours. Poetry, like any public creative act, is deeply communal. The minute a poem leaves your hand or your mouth, it belongs to its audience.

How do you define success?

To me, success in poetry is about resonance. Did this poem touch someone’s heart? Did this poem influence someone’s mind? Did this poem make someone think differently about the world, did it comfort them, provoke them? If someone can shrug their shoulders and ask ‘so what?’ after hearing a poem, I consider that poem to have failed.

Do you ever regret sharing your work publicly? Do you trust the reader in a world of instant gratification and instant communication?

No. I’ve published work and then decided in a few years later that I no longer agree with my thoughts, but this is a sign of growth, and not something to regret. I don’t know if it’s a question of ‘trusting’ the reader. People take what they need from poetry. All you can do is write from your heart and publish your work with hope and in good faith. The rest is kismet.

You can buy Amani’s poetry collection SPLIT here